“Numbers on the Board” is a monthly column inspired by Walt Hickey’s Numlock News, adapting that format for the music business. A dive into the numbers headlining and defining stories of interest.

—

24 weeks - Kendrick sets a Billboard record

Another milestone in a career year for a generational artist. At this point, there’s little more to add to the story of Kendrick Lamar’s resurgent superstardom.

In the beginning of October, Lamar’s “Not Like Us” broke the Billboard Hot Rap Songs chart record with 21 consecutive weeks at number one. It just finished its 24th week in the top spot. While ascendant songs by GloRilla and something from Tyler, the Creator’s new album CHROMAKOPIA might challenge, it feels like “Not Like Us” will continue to create distance from previous record holder Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” (20 weeks).

A brief thought on the nature of this sort of record. While musical achievement in the streaming age feels a bit like home run tallies during baseball’s steroid era (i.e. inflated), there is something objectively impressive about holding people’s attention long enough to top a chart for 46% of a year. With a Super Bowl performance on the horizon it seems “Not Like Us” could simply continue its reign, already achieving a cultural permeation that feels greater than almost any of Lamar’s other big songs. Such dominance is especially impressive in an age of tremendous noise and short-lived hits (though, perhaps, this is the paradox that allows a superstar with a signature hit to dominate in an otherwise noisy landscape surrounded by less memorable songs).

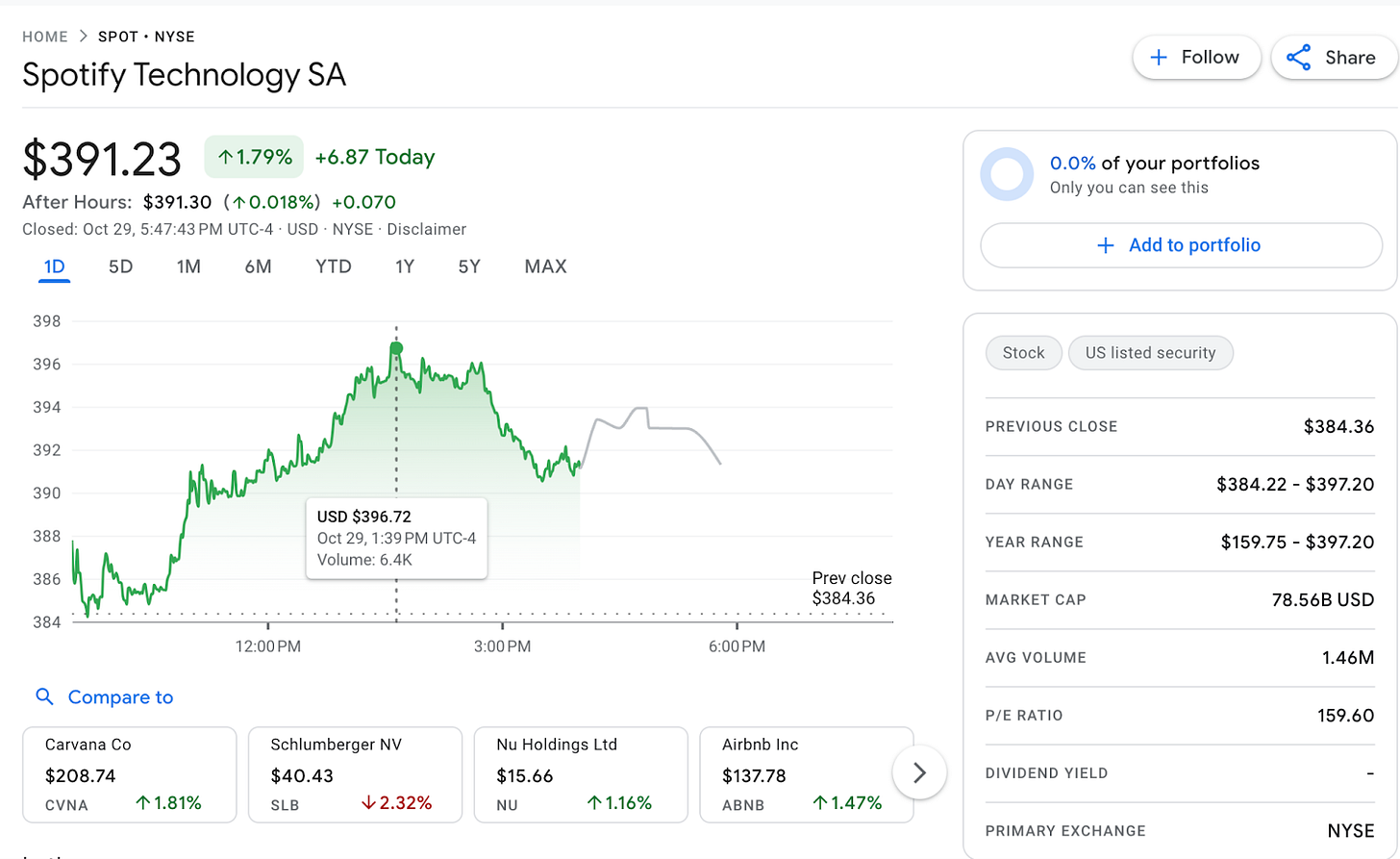

$397.20 - Spotify hits record high share price / The unbearable lightness of laying off 1500 employees

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine sent me a screenshot of a bespectacled Daniel Ek next to the headline “Spotify CEO Daniel Ek surprised by how much laying off 1,500 employees negatively affected the streaming giant’s operations” (the image that leads this edition of this column).

Naturally, I thought this was a joke.

Alas, it was an actual article from April 2024. (Ironically, this article is behind a paywall and, no, I am not subscribing to find out about Ek’s surprise. It is far funnier imagining.)

As I put the finishing touches on this edition, Spotify had touched a record stock price of $397.20 a share on October 29th, with analysts predicting room to grow. This bullish outlook must owe in part to Spotify’s rising audiobook market share, a new strength alongside their dominance in music and podcasting. The company that resurrected the recorded music business is now simply an audio hub with a mass of paying users.

Of course, in America growth alone cannot inspire runaway investor confidence. Nothing juices stock prices like finding fat to cut from the ol’ P&L, pensions, vested stock, and general livelihoods be damned. The ironies abound: While layoffs affected app functionality and daily operations, it’s clear that neither of those things has proven mission critical to the generation of shareholder value.

$8-$12m - Coachella headliners

In July, I looked at the trend of festival cancellations in England and the broader raft of concerns underlying an uncertain live market. Costs form one of the least controllable problems facing well-established festivals and upstarts alike. When considering them in July’s Numbers on the Boards, I mostly thought of infrastructure and labor costs. I thought less about talent.

Bloomberg’s Lucas Shaw broke the news that Kendrick Lamar and Rihanna both turned down Coachella headlining spots in 2025. The former is playing the Super Bowl and planning “a tour of major stadiums” after, in conjunction with rumors of new music. The latter is Rihanna and doesn’t need to do a fucking thing. Shaw expands:

“Yet booking A-list acts has grown harder in recent years. While major musicians headline festivals for lucrative paydays, the biggest acts in the world today can now make more on their own. Promoters and ticketing companies have figured out how to increase prices to record highs. While Coachella pays headliners $8 million to $12 million for the two weekends, Beyonce and Taylor Swift now gross as much as $15 million a night – and with better profits.”

This sort of cost inefficiency further reinforces my belief that the next five to 10 years will see a rise in niche festivals and smaller enterprises that attempt to recapture the original spirit of Coachella in all its scrappy, genre-mixing glory.

84% - proportion of TikTok users following small and mid-tier accounts

75% of popular songs on TikTok started with a creator marketing campaign

It is hardly breaking news that the current media landscape has a far more disjointed feel than in almost any decade since the dawn of television (perhaps the beginning of the concept of modern monoculture). Two statistics about TikTok bring stark light to what might have seemed contradictory notions even a decade back:

While big media outlets still matter, they are battling for space in the same way every creator, big and small, seeks attention in the current climate. The phrase “attention economy” has dominated media thinking for the last decade, but to see that borne out numerically by Pew Research Center’s analysis (pictured above) makes our present fragmentation crystal clear.

Regardless of how fragmented TikTok is, it is the new broadcast media. And, like all broadcast platforms before it, it’s going to be subject to heavy amounts of money getting poured into any and every thing promoted on the platform. Exhibit A: Billboard’s report that 75% of popular songs on TikTok began with some sort of paid marketing campaign.

On the one hand, these statistics mean that big IP owners (major labels, movie studios, video game publishers) don’t control the same dominant distribution channels that they used to, suggesting a more democratic, organic environment for virality. On the other hand, these entities and their proxies (digital agencies/marketing companies, managers, agents) still pay vast sums to promote content containing their IP, leading to dispersal of funds into many more hands (individual “creators,” small “publications,” and all manner of other non-traditional channels on TikTok and similar platforms).

Taken in a vacuum, neither of these statistics is particularly interesting. Taken together, they are a snapshot of an unprecedented media reality, one in which platforms are conduits controlled by their users, where programming is (ostensibly) not shaped by a central hub of decision makers, and where money flows freely and with little regulation to those capable of drawing attention. This landscape has largely dictated the nature of music marketing in the last few years and seems to be peaking in its efficacy. Conversations with A&R’s and marketers alike point to a general “no one knows anything” attitude across the business. At the same time, 2024 has been littered with more traditional success stories. While new stars Shaboozey, Chappell Roan, Sabrina Carpenter, and Benson Boone have seen their hit songs bolstered by social media, they have all put out tons of music over many years, toured extensively, and, in the case of the first three, been dropped by or moved on from their previous labels before achieving stratospheric hits.

When a business or set of ecosystemic conditions are this fragmented, it typically means consolidation and/or regulation are around the corner. With TikTok under continual scrutiny from the US government, the latter wouldn’t surprise me.

I’m more curious about the former.

It is easy to imagine what the reunification of television looks like. In the coming years, companies like Apple or Amazon could cut bait on unprofitable film/TV studio businesses and push to become aggregation solutions for the disparate apps and services that “unbundled” cable. These existing incumbents that could use their distributive might to force the hands of content owners, setting a logical (though perhaps farfetched) path to consolidation. It is much harder to imagine how TikTok coalesces into the new radio, unless we simply admit that the non-interactive broadcast paradigm is dead and gone forever. Terrestrial radio’s much prophesied slow death has not yet come to bear, so I doubt social media will replace it within the decade.

250,000+ - Tyler, the Creator’s CHROMAKOPIA first week album sales

On November 8th, 2010, I saw Odd Future perform their first New York show at The Studio at Webster Hall. Packed into a tiny underground annex for the venerable, a bursting crowd screamed almost every word back at Tyler, the Creator and his band of Los Angeles rogues. In the age before I had a camera phone, my only keepsake was a massively oversized white OFWGKTA (an unwieldy acronym for the rallying cry “Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All”) t shirt I snatched from mid-air in a hail of merch flung from the stage.

At some point in the evening, Tyler shouted “Fuck every label and magazine here, suck my dick!” to a room bordered by the many A&R’s and magazines who would chase him in the coming months, invoking a set of corporatized zombies as exactly the sort of perceived enemy that fires up a crowd of diehards.

To date, Tyler and his loose collective had built a rabid following through free mixtapes, downloadable from their Tumblr. Earl Sweatshirt, one of the pillar members of Odd Future’s moment, was missing. (Reported to either be in juvenile detention or grounded at home, it turned out Earl had been sent to a Samoan boarding school by his mother after the release of his profoundly vulgar, viral mixtape EARL). “Free Earl” and “Fuck Steve Harvey!” chants rang throughout the night. A pre-show DJ set by Nick Catchdubs nearly set off a riot with Waka Flocka’s “Hard in Da Paint” and The Diplomat’s “Dipset Anthem.” Hip-Hop existed in a kind of chaotic transition, with single-focused artists like Flo Rida dominating sales, album-oriented artists like Kanye West reshaping culture, and artists like Lil Wayne and Drake bouncing between jaw-dropping raps and treacly pop in equal measure. Blogs and the nascent rap internet secured many emergent artists major label deals, but few managed to break through commercially after signing.

To glimpse Odd Future from that crowd was to see something that felt like a grand beginning. And yet, their music was abrasive, raw, and often hateful (their early projects are particularly homophobic and rife with punky provocations like “kill people, burn shit, fuck school” and references to themselves as Black Nazis, a topic I wrote about in 2012 and one that I could certainly discuss today with greater insight). Their aesthetics defied mainstream gloss. Their music sounded like a cross between Eminem, MF DOOM, and Pharrell’s more experimental tendencies, hardly the stuff of major label mood boards in an era dominated by Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, and the Bar Mitzvah-fied version of the Black Eyed Peas. They had sold out a 150 person venue. Could they sell albums?

Next week, Tyler is set for the biggest first week sales of his career as his new album CHROMAKOPIA lands somewhere between 250,000 and 300,000 units. With the exception of his third studio album Cherry Bomb, each of his seven albums has had a bigger first week than the one before it. His last two albums (IGOR and Call Me If You Get Lost) each debuted at #1 on the Billboard Album chart. CHROMAKOPIA will likely do the same. His is an arc like few others in music, a lesson in world-building and commitment to a singular vision worth studying (though profoundly difficult to emulate). While Odd Future disintegrated and only launched two superstars (Tyler and Frank Ocean), its legacy remains a lesson in audience cultivation, embodied in Tyler’s ever-more popular music, his clothing empire, and his festival, Camp Flog Gnaw, now in its 10th year.