Numbers on the Board (July 2024)

“Numbers on the Board” is a monthly column inspired by Walt Hickey’s Numlock News, adapting that format for the music business. A dive into the numbers headlining and defining stories of interest.

$49 million annually - Queen’s catalog revisited

Another month, another set of thoughts on a recently sold catalog. While Sony’s $1.2b acquisition of Queen’s recorded music rights, publishing rights, and name/image/likeness rights is staggering by any measure, a recent report makes it seem partially de-risked. Music Business Worldwide reports that the catalog earns $49 million annually. Assuming no growth and steady income (which feels safe to predict for a catalog of this age and scale), that means Sony will hit a crossover point into profitability in 24 years. While that might seem like a mighty long time, it is a relatively safe bet that annual revenue won’t simply stay at that level given Sony’s ability to exploit the full scope of Queen’s IP rights and the continued growth of the streaming and sales markets more broadly. Even still, making a billion plus dollar investment with a very clear path to profitability is welcome and unusual in any industry, so news like this provides a window into why companies like Sony, UMG, Warner, Primary Wave, Hipgnosis, and others are willing to take astronomical bets on proven works and brands.

To this end, I’ve started yet another experiment that is going to take a bit more effort and time than my dalliances with Grammy winning album length and hit song length. A bit of background, then an explanation.

In 1997, David Bowie presciently bundled his rights in a security backed investment vehicle that came to be known as the Bowie Bond. Valued at $55m, it was roundly regarded as a disaster in its time, mostly due to the Napster-driven downturn in the recorded music business that followed its introduction. Even at the inflation-adjusted rate of $107m (by 2024 dollars), the Bowie Bond was still underpriced compared to the $250m price tag Bowie’s catalog fetched upon sale in 2023.

I am working on something I’m tentatively referring to as “The Bowie Index.” It’s a formula designed to provide a comprehensive and scalable measure of the value of rights deals, focusing on master and publishing catalog sales, but also including name, image, and likeness rights where applicable. It incorporates multiple key factors, each scored exponentially, to reflect the potentially uncapped nature of a deal's value. The formula includes:

Purchase Price (PP): Actual purchase price.

Suggested Purchase Price (SPP): Estimated using industry standard multiples for sound recording (typically around 5-10x annual revenue) and publishing catalog sales (typically 12-15x annual revenue) and annual revenue.

Annual Revenue (AR): Average annual revenue generated by the catalog.

Nature of Rights Purchased (NRP): Scores for different rights (Master, Publishing, NIL), adjusted for partial ownership.

Type of Right (ToR): Score based on whether rights include revenue streams alone or ownership of the underlying copyrights.

Technological Shifts Factor (TSF): Adjusts for positive or negative impacts of technological changes.

Purchase Price Adjustment Factor (PPAF): Ratio of SPP to PP.

I am currently working out how best to account for inflation and technological shifts that might affect revenue negatively or positively. As an example: Napster arrived in 1999, leading to the massive devaluation of commercially available music. Spotify launched in 2006, resuscitating the value of commercially available music around 2015/2016, only to announce in 2024 that its new bundles spread its subscription revenue across other types of non-music audio, once again reducing royalties paid to music rights holders. I am mostly developing this model for fun, but I’m also attempting to gain a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes a “good” or “bad” catalog deal in a landscape where players so often bend to the irrationality of market share dominance and “me too” logic.

As I refine the formula incorporating these inputs, I’m going to share it in this newsletter, then apply it to deals with publicly available data. This process will be imperfect; often these deals are shrouded in mutual NDA’s. I will likely test the model on data privately available to me. For myriad reasons I will not be able to share some of those findings in anything but a heavily redacted way. I am highly open to feedback about suggested methods or existing approaches to catalog appraisal, if anyone cares to reach out. I’ll report back as anything interesting pops up.

50 Cancellations - the problem with festivals

In the April edition of this column, I looked briefly at Coachella’s “struggles.” While dipping sales and slower sellouts surely don’t spell immediate doom for the stalwart SoCal festival, its slight waning feels atmospheric at this point, not isolated. Witness the cancellation of over 50 festivals in the UK. Former Spotify chief economist Will Page’s Music Business Worldwide op-ed posits five potential reasons for this rapid spate of cancellations:

ISSUE 1: COSTS – RISING BEYOND THE PROMOTERS’ CONTROL

ISSUE 2: SUPPLY – AN EMPTY FIELD OF NICHES?

ISSUE 3: DEMAND – GO REALLY BIG OR STAY HOME

ISSUE 4: CULTURE – SOCIALS DON’T SOCIALISE IN FIELDS

ISSUE 5: JUST BLAME THE WEATHER

I touched on a few of these ideas in April. That there are only so many superstars with truly universal draw (a point explored in depth on a recent episode of Popcast). That niche programming forms a big part of the present and may define the future. That costs passed down to consumers are becoming untenable.

We are living through an era of great economic cognitive dissonance. In America, certain signs point to abundance. Per a recent tweet by Ben Wikler, chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party: inflation is falling, crime is falling, border crossings are falling, climate emissions are falling, inequality is falling (whatever this means), energy production is growing, real wages are growing, jobs are growing, unions are growing, and the stock market mostly continues its upward ascent. Last week, the New York Times echoed this general upswing, reporting 2.8% growth owed to increased consumer spending on the back of a strong labor market and lowering inflation. These observations are hard to square in a country that is also experiencing record credit card debt defaulting, a crisis of elderly care, and the continued, crushing wave of layoffs and company restructurings that has colored so much of 2024. 40 million Americans live below the poverty line, with a third of all citizens saying they are not sure how they’re going to afford rent (per Throughline). Thirty percent of all renters spend half their paycheck on rent. That is to say nothing of the uncertainty embodied in the upcoming presidential election. Consumers fearing local and global upheaval will probably continue to eye supremely disposable purchases like festivals skeptically, a knock-on effect of broader conditions that may undo years of planning and infrastructural work on the part of concert organizers.

We are at an inflection point where the age of the infinitely growing broad-spectrum festival comes into question. Some will survive, most will not.

Simultaneously, this sort of doom stands in direct opposition to the growing windfall of the live music business. Per friend and old basketball nemesis Lucas Shaw’s Screentime (which I’ll quote again later):

“The pandemic suppressed dealmaking. The live-event business shut down overnight and then spent a couple of years rebuilding. Uneven financial results make it hard for a banker or buyer to assess value. Consider Live Nation Entertainment, the largest ticket seller and concert promoter. Here are its sales for the last five years

2019: $11.5 billion

2020: $1.9 billion

2021: $6.3 billion

2022: $16.7 billion

2023: $22.7 billion

How are you supposed to build an investment model off of that?

But the business has recovered from Covid-19 and by many metrics looks stronger than ever. Whether it’s live music, theme parks, sporting events or even stand-up comedy, live entertainment is breaking records.

That makes it appealing to all kinds of investors.”

People are back outside and spending money. But they’re also scraping by in the face of some of the most challenging economic conditions of the post-World War II era. How do we make sense of these opposing facts?

$10 a month - fair rate for artists?

In his first Screentime of July, the aforementioned Lucas Shaw took questions from readers. One of those questions and Lucas’ response below, in regards to the constant conversation about artists being paid fair rates for the consumption of their music:

“What price would Spotify and other services have to charge for artists to earn the same money they made at the height of the recorded music business?

About $10 a month. This answer may surprise you because the average price of Spotify in the US is higher than that. But the average price of Spotify globally is just under $5.

Music industry revenue peaked in 1999 at $22.3 billion. That translates to about $42 billion today. Global industry sales last year totaled $28.6 billion. So we’d need to find another $13 billion to $14 billion.

That is the exact size of the paid streaming market today ($13.8 billion). So if you doubled the paid streaming market, the business would be as big as at its peak.

This isn’t an exact answer, of course. I can come up with all sorts of caveats. But I will answer the question with a question. Would you pay $25 a month for Spotify?

Don’t worry, you won’t need to any time soon, though Spotify is raising prices.”

While I think Lucas’ answer is great and historically illuminating, I have some issues with the basic premise of the question.

As Spotify bundling pummels songwriter royalties and new tech companies arise with a hunger for music accompanied by an aversion to paying for music, the question of what constitutes fair value for sound recordings and copyrights will amplify considerably.

Lucas’ heavily caveated proposal may be difficult given economic realities worldwide, but it is not hard to imagine Spotify’s subscriber base continuing to grow to levels that partially offset the royalty diminution of its bundling tactics. This question also doesn’t account for the notion, nebulous as it might be, that new consumption formats will come along and add value to music in previously unimaginable ways, just as streaming did.

For all the pontificating about what Spotify has done to devalue music and the work of those who make it, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that the music industry would not exist without Spotify. Beyond vinyl’s unexpected resurgence, streaming’s transformation of the music industry constitutes the singular success story of recorded music in the last 20 years.

That is not to hand wave its inherent problems or pretend that we are in a golden era of consumption. Spotify has not created utopian conditions where all artists get paid living wages (or more) for their creations. Good curation and satisfying discovery persistently form moving targets.

Still, streaming made music valuable again, full stop. It stanched the bleeding started by Napster and showed major labels, independent labels, and artists alike a new path for monetizing their music. In the last month alone, I’ve had a number of conversations about how unpredicted streaming behaviors have led to some marquee catalog deals overperforming economic expectations.

My other problem with this question is the notion of artists being properly compensated to begin with at some previous point in the history of recorded music. We don’t need to spend too much more space discussing the constant, structural disadvantages record and publishing deals visited upon generations of artists at all scales. Let’s look at songwriters in particular. As a songwriter in the 1970s, 1980s, or 1990s, if you had a song anywhere on a massive selling album, you were likely going to make a lot of money. The person who wrote a deep cut on, say, a Backstreet Boys or NSync album would have a far more lucrative composition on their hands than many co-writers of big hit singles these days. The reason for that: Hit artists in the pre-Napster era sold tons of physical albums, and physical albums pay statutorily mandated mechanical royalties rates to songwriters that are much higher than streaming (digital) mechanical royalty rates. That remains true today. If you work with an artist who sells a lot of vinyl (a la Taylor Swift), you benefit from the resurgence of physical product. Still, this windfall has almost always applied solely to those involved with the highest echelon of artists, to say nothing of the artists themselves. Making a living in music as an artist, producer, or songwriter has never been sure. Any notion of its ease in a bygone era is a mirage. If anything, the playing field has grown more level as talent has grown to understand its leverage more and a greater body of tools exists for valuing creative work and negotiating better deals. While this moment in music is as crowded and difficult as any, it is also rife with new kinds of monetization opportunities that were unimaginable prior to 1999.

Again, I’m not defending Spotify, TikTok or anyone looking to pay nothing for the use of music. At some point, though, we have to assess the question of earnings through the prism of potential and not just hard and fast questions of rates or consumer pricing. These factors are crucial, but they’re not sole determinants.

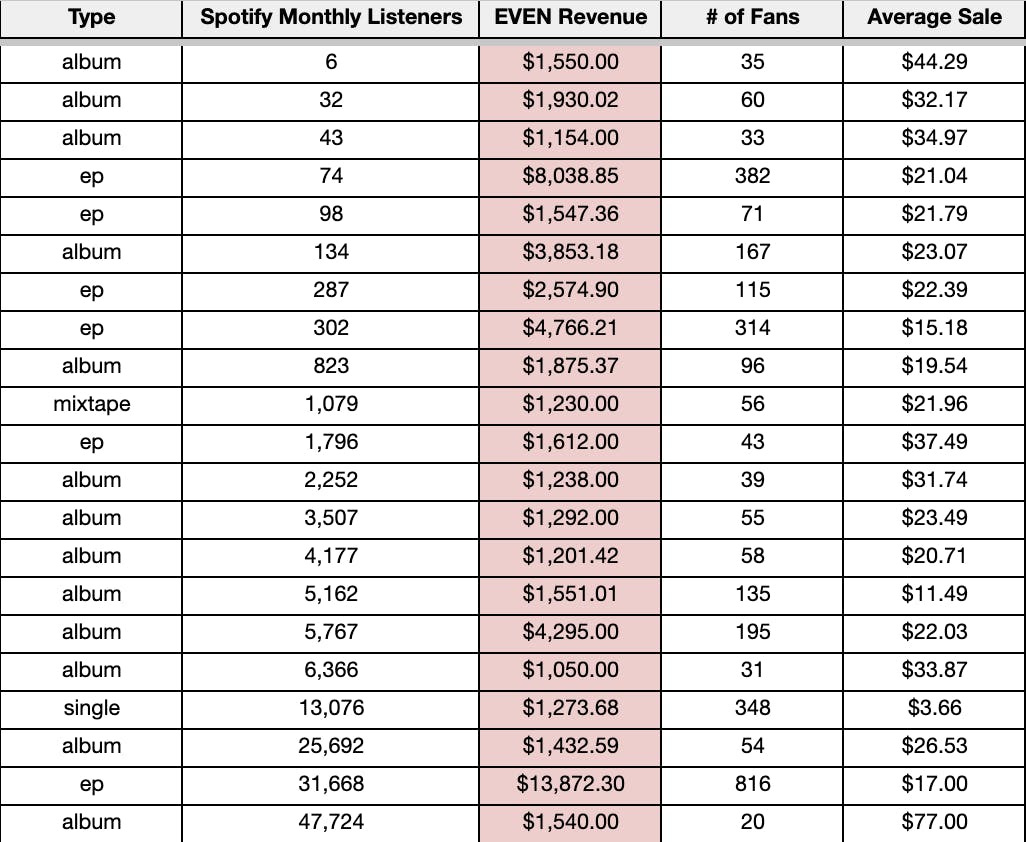

It is worth noting as well that other companies and thinkers approach this notion of how artists capture value for their music from a different lens. Direct-to-fan startup EVEN touts tools for better capturing dedicated fans and selling music to them. Its founder Mag Rodriguez shared the following table in a recent newsletter, logging “artists on EVEN—many with fewer than 10K monthly listeners [on Spotify]...making thousands of dollars.”

While this sort of chart cannot tell the entire story (what, for example, did it cost these artists to make these EPs, albums, singles, and mixtapes?), it points to one of the many alternatives that exist for artists looking to build outside the hegemony of Spotify.

55 Years - Iconic Hollywood studio Record Plant to close

When I moved to Los Angeles in 2014, Record Plant was the first famous studio I had the privilege of visiting. I wondered at the time how any studio of this stature could still exist, multiple posh rooms cranking through days and deep into nights, electricity, bottled water, takeout, and alcohol fueling attempts to power through one of music’s murkier economic periods.

A decade later, with many signs pointing to the continued growth and prosperity of the music industry writ large, Record Plant is shutting its doors. This closure comes at a time when many of Los Angeles’ studios seem, at least anecdotally, busy as ever, particularly when it comes to high profile projects.

Yet facts loom large: More labels have built their own studios, some artists and producers favor home studios, and, even for the aspirant, it has become easier to make music in any environment than ever before thanks to mobile technology that goes up in quality and down in price each year.

Still, Record Plant’s end seems out of step with broader industry trends and the conversational observation that many marquis Los Angeles recording studios (such as Henson, EastWest, and Conway) remain booked out, with some rooms being occupied for months at a time.

I was never a studio cookie guy, but I remember Record Plant’s being particularly good.