Applied Science #6: Publishing Simulator

"She asked how much publishing I made off of my BMI" - Big Sean

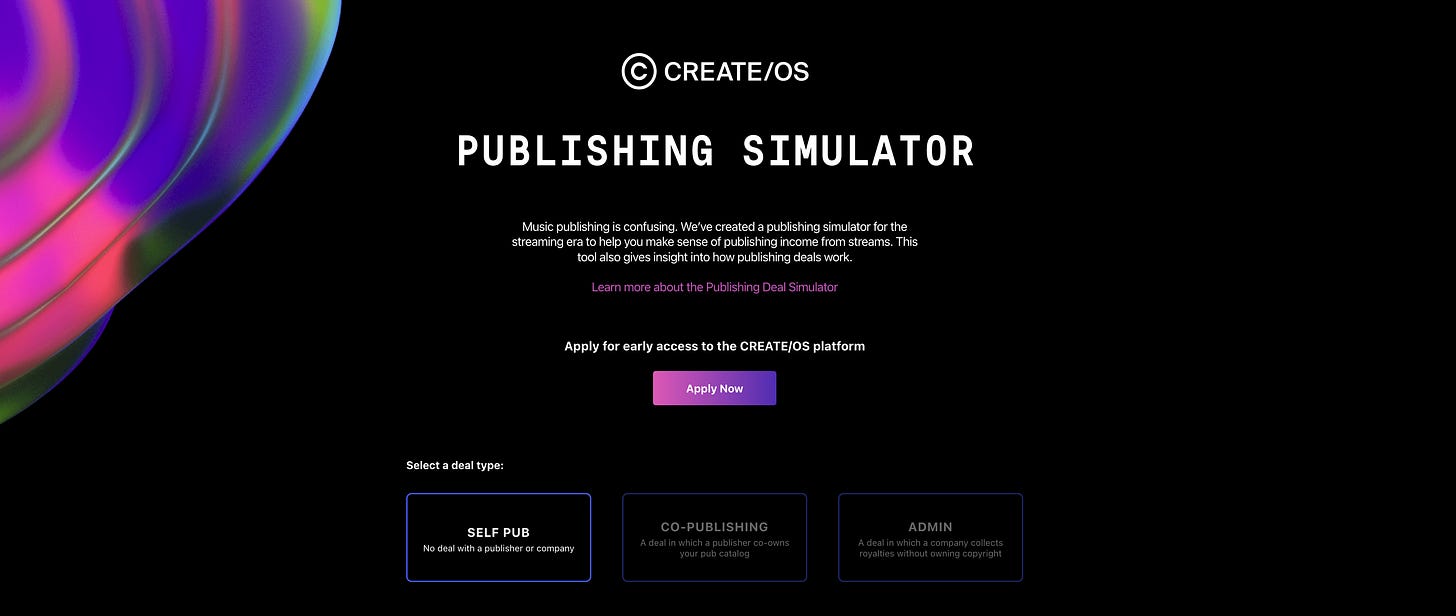

CLICK HERE TO VIEW PUBLISHING SIMULATOR. LEARN MORE BELOW.

"That paper it get funny when publishing is involved

Mechanicals never mattered because that was your dog

Now you hands-on, but things don’t ever seem right

You make a call to give your lawyer the green-light

He look into it then hit you up with the bad news

It’s so familiar, he did the same with the last dudes”

- Rick Ross, “Foreclosures”

In September 2020, CreateSafe introduced the record deal simulator. Our goal: Simplifying a complex concept with a visual model. Now we’re applying that same framework to one of recorded music’s great minefields: Publishing.

In the last few years, music publishing catalyzed animated conversation and much confusion. As private equity firms, established music companies, and ravenous hybrid entities snatch up catalogs in a land grab, mainstream press has covered the value and meaning of publishing rights with previously unseen depth and pace. Upstart entities like Hipgnosis battle with Universal Music Group, Sony Music, Warner Music in a clash of the titans over who gets the right to put a Bob Dylan or Neil Young song in some car commercial in 30 years (the answer: Universal for Dylan, Hipgnosis for Young). Marketplaces like Royalty Exchange allow private investors and armchair observers to purchase pieces of songwriters’ revenue streams. The story spills beyond the pages of the trades, into Bloomberg, the Financial Times, and The New York Times—romantic artistic notions giving way to pure commercial considerations as a predictable new asset class emerges.

Public curiosity aside, publishing remains frustratingly murky. It is thorny, ever-evolving stuff in the digital age; its origins and financial aspects could fill book-length explorations, difficult to briskly distill.

Fool that I am, I’m going to try.

Publishing & Hamburgers

As a songwriter, you probably don’t know that you need a music publisher. At very least, if you want to collect the publishing revenue generated by your music, you’ll need an administrator or some intermediary set up to gather that money.

Very little about modern music publishing is intuitive. When you start releasing music, you don’t receive an automatic warning about potential lost income. You might have been told you need to sign up for a performing rights organization (or PRO; in America, these include ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, and GMR). That only covers a piece of the pie. A manager or lawyer might inform you, but some young managers might not know themselves. Some lawyers might assume you’re already aware if you don’t ask questions.

You don’t have to do a deal with a major publisher, or do a deal with an independent publisher or administrator. Numerous new companies now do the job for a fee (Songtrust, for example, offers a very flexible administrative service for a $100 flat fee with a 15% admin rate; Symphonic offers a similar service). If you don’t want that money to disappear into a mysterious black box, someone has to collect it on your behalf.

Before understanding publishing in concrete terms, it’s important to explore it conceptually. No single metaphor stands for publishing. The closest I can muster is the recipe and the finished dish.

A hamburger is a wad of meat, typically flat, generally served on a bun with lettuce and a tomato slice. It’s an iconic entry in sandwich history with a beautifully simple recipe: get ground meat, flatten, grill/fry/sauté/broil, place on bun, serve. This recipe at its most basic has existed in some recognizable form for almost 150 years, a staple of fast food restaurants across the globe.

If you’ve ever been stuck in a conversation about hamburgers with a Los Angeles native, you probably know that simple recipes can cause serious debate. You’ll likely be told that In N’ Out, the famed California-born chain, is better than any competitors, better than global behemoths McDonald’s and Burger King, better than Five Guys, and certainly better than New York infiltrator Shake Shack. All these restaurants serve hamburgers, but with key variations that inspire fierce partisanship (the correct answer for L.A. residents is actually Apple Pan).

A recipe is a lot like a composition—the lyrics and melodies that make up a song on paper. The sound recording (also commonly called the “master,” but we’ll stick to sound recording here) is like a finished dish—the thing served to and consumed by the customer, audio memorialized in physical or digital form.

In the hands of different artists, producers, and musicians, notes and words on a page can take on new life. The rollicking soul of Gloria Jones’ “Tainted Love” (1964) becomes the bouncy, dark synth pop of Soft Cell’s lone hit “Tainted Love” (1981), and then again morphs into the metal dirge of Marilyn Manson’s “Tainted Love” (2001). The same song served three ways (and, importantly, sold as three discrete sound recordings), same basic ingredients tweaked, unified by their conceptual foundation.

As effortless as hamburger-making might seem, it requires a basic recipe—a minimum set of agreed upon ingredients. Whether you write it down or commit it to memory, the recipe hovers in background and finds its way invisibly into the finished dish. Conversely, you can always take a classic recipe and dress it up into something almost unrecognizable (like L.A. beer-and-burger joint Father’s Office does with their hamburger, which is essentially a ground beef sandwich packed with caramelized onions, arugula, and blue cheese—a burger in the same way that Marilyn Manson’s “Tainted Love” is Gloria Jones’ “Tainted Love”).

A finished dish is to a sound recording, as a recipe is to publishing. You can have a recipe without a dish, but you can’t have a dish without a recipe. You can have publishing without a sound recording. You can’t have a sound recording without the underlying published composition.

Compositions form the core of music publishing, the copyrightable intellectual property at the heart of every song. Notes on a page form one of music’s steadiest potential income sources—a font of residual royalties that can last years and lead to considerable catalog sales (there’s much to say on this topic; Pitchfork recently published a solidly comprehensive state of play in the catalog market). Of course, each time you make a hamburger at home, you don’t need to pay royalties to the inventor of the hamburger or the founder of In N’ Out. You might own a cookbook or two that led to a chef earning some royalties, but you’re free to cook dishes as many times as you’d like without owing anything extra to the meal’s originator. Here the metaphor breaks down a bit. When Gloria Jones, Soft Cell, and Marilyn Manson sing “Tainted Love,” the song’s publishing royalties go to one person: Ed Cobb, the song’s sole writer. Since Cobb passed in 1999, the royalties likely flow through an administrator to his estate; when you hear “Tainted Love” on the radio, in a restaurant, or in a film, it means that someone who represents Cobb is earning money for the recipe Cobb created almost 60 years ago.

But why divide sound recording and publishing income?

A few years ago, Chance the Rapper provided an explanation of publishing and sound recording during a conversation at the University of Chicago (video below). He rightfully mocks the confusing division. Put poetically: “none of that shit makes any sense,” a dismissal inspiring a wave of laughter and applause. While it might not seem logical in an increasingly digital reality (in which every play could be considered a disembodied use) and it is undoubtedly quizzical, historical context explains words that he glibly casts aside as dated and empty.

Before you could purchase a phonograph and play your favorite recording at home, what you might have done (if you had a piano and some money) was purchase sheet music to popular songs. These songs had lyrics (written by a lyricist) and melodic compositions (written by a composer). Sometimes the lyricist and composer were one in the same, many times not. These songs would be compiled by publishers, who organized, printed, and distributed sheet music for sale. Right here, you can find the genesis of one of the most confusing aspects of publishing. Anyone who signs up for BMI or ASCAP is prompted to create either or both a “songwriter” account and a “publisher” account. When publishing income is derived from a song, that income breaks in half, forming a “writer’s share” and a “publisher’s share.” This notion derives from the literal division between the people who wrote the songs and the people who published them on paper or in booklets. In the Internet age, this bisection of songwriter and publisher feels antiquated, a relic of a time before Ableton, Pro Tools, Apple Notes, and Tunecore could turn anyone into a self-published producer, songwriter, and artist all-in one. The digital age has further confused people about the notion of what a “songwriter” is to begin with, but we’ll address that separately.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the first commercially available recordings appeared in stores and the homes of eager listeners (Gareth Murphy’s Cowboys and Indies provides a fantastic recounting of this history). These records hardcoded the split between the sound recording and the composition that still informs our understanding. Two recordings could embody different versions of the same composition. Let’s use our tried and true example, “Tainted Love” by Soft Cell and also “Tainted Love” by Marilyn Manson. The label for the first recording (Mercury Records, now a subsidiary of Island Records, itself a subsidiary of Universal Music Group) would earn income from the sale of its recording (“master” revenue), while the label for the second recording (Nothing/Interscope, also a subsidiary of Universal Music Group) would earn income for the sale or streaming of its recording—the songwriter and publisher of the song would earn income from both recordings, because each made use of their intellectual property (Ed Cobb’s catalog does not appear to be published by Universal Music Group’s publishing company Universal Music Publishing Group, but if it was, UMG would be earning publishing income from the song as well).

Publishing also governs income from disembodied uses, a confusing and oddly violent term describing songs being used separately from their context on a single recording or album or in the form of an on-demand stream. Disembodied uses cover radio plays, live performances, sync licenses, and broadcast licenses (for plays in restaurants, in stadiums, on live television). Defining “disembodied” presents increasing philosophical issues in the digital age, as companies like Spotify and Apple combine both “on-demand” and “lean-back” streaming—services providing two modes of listening that used to be split between purchasing a CD, record, or tape (“on-demand”) and tuning into the radio (“lean back”). This division has come under particular scrutiny, as companies as disparate as indie vanguard Beggars Group, German media giant BMG, and aforementioned upstart Hipgnosis all push for greater transparency from Spotify regarding what listeners are actually engaging with on their platform. That data might be a matter of many millions of dollars.

Why we built the publishing simulator

The publishing simulator is an educational tool for understanding how money flows to songwriters when it’s generated by digital streaming—and how different deal types can affect that flow. As with the record deal simulator, it is an attempt to simplify and visualize conceptually thorny things. Record contracts can be impenetrable tomes, but it’s relatively easy to depict the sources of income record labels and distributors collect. Publishing tends to be more muddled, encompassing more revenue sources (many of which are harder to accurately track), governed by more statutory requirements, and complicated by a global music market whose territories operate under disparate rules. Much information regarding publishing royalty rates (such as per-play rates for radio spins) is either treated as proprietary (walled-off by expensive metric trackers like Nielsen and Mediabase), tough to accurately assess from publicly available information, often requiring reverse-engineering from royalty statements and consumption data.

We limited the scope of the publishing simulator to cover the same economic terrain as the record deal simulator. The publishing simulator only encompasses income from digital mechanical royalties and digital performance royalties (as the record deal simulator only covered digital master income). We excluded sync royalties and fees once again. While syncs can generate significant income for producers, songwriters, and artists, and sync licensing houses can generate healthy incomes for non-superstars, sync income tends to be too sporadic and piecemeal to project linearly (as is the intention of the various sliders in these simulators). As an example, a client of mine landed the biggest sync of their career in 2018. It would be another two years before any sync even came close—that’s not even that long of a time, but it’s an eternity if you’re trying to make predictions about your income and plan around your expenses.

In publishing simulator’s resting state (unpublished), we assume that a songwriter has signed up for a PRO (something all songwriters should do), but does not have a deal with a publisher or administrator. As a result, only a portion of the writer’s publishing income is being collected on their behalf and passed to them; some of that income would require an assigned entity to ensure its proper collection. In co-publishing and admin states, we assume the songwriter has signed up for a PRO and has done a deal that assigns a company the right to administer a songwriter’s catalog and collect royalties on their behalf. In the latter states, the songwriter earns a portion of income directly from their PRO; the songwriter will not earn income on the part of their catalog administered by a publisher until they’ve recouped their advance. If a songwriter is considering doing a publishing deal, the co-publishing and admin states will help them understand the mechanics of streaming income in that agreement.

Our emphasis on streaming royalties aligns with a focus on the people who might find this tool most useful: emerging artists, songwriters, producers, and managers. While you could use the publishing simulator to model a portion of your income under the terms of a given deal, its current limitations would make it impossible to map the full scope of your income in a typical co-publishing deal or admin deal.

The record deal simulator and publishing simulator form a functional interface for understanding the financial mechanics of recorded music deals and income in the streaming age. They should provide a helpful back of the envelope calculation for digital recorded music streaming income in different scenarios. The hope is that these kinds of tools clarify complex deals and royalty statements.

The visual unification of this financial information is another step in piercing the music establishment’s steel curtain. Confusing language and unfamiliar concepts have been used for decades to dupe artists (or, at very least, to establish extractive relationships that can seem advantageous until the nature of their lopsidedness becomes clear in the course of years or after some singular incident). The publishing simulator and record deal simulator are in-progress pieces of a larger puzzle—one that includes plain-language contracts and greater adoption of collection-oriented tools and services like Paperchain, the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC, a new organization established by the Music Modernization Act for collecting digital mechanical royalties from DSPs), and ASCAP and BMI’s newly launched Songview, a years-in-the-making project that should have exists decades ago. These projects speak to the unsexy reality at the core of almost all royalty-related issues (and one that seems central to BMG’s recent “ground-breaking” investigation of its own participation in racially-driven royalty injustice): Payment can often be boiled down to a problem of cataloging and understanding metadata.

Metadata is the information that enables copyrights to be trackable and valuable, the mundane lifeblood that allows publishers to collect money and know who it’s supposed to go to in the first place. It encompasses information like artist names, track titles, songwriter/composer names, track lengths, releasing label or distributor, release date, and the like. All companies that own or administer rights use metadata to determine who gets paid and what they’re owed. Every creator should be able to simply track their metadata from creation to commercial exploitation and readily comprehend their projected and potential earnings, whether they’re releasing through Tunecore or one of Universal Music Group’s numerous subsidiaries. (When Universal buys Bob Dylan’s publishing catalog, they are, in essence, buying his data). Visualizations of the flow of earnings via tools like the record deal and publishing simulators give everyday creators the capacity to understand the kind of royalty discrepancies that would previously have taken decades, public moral outrage, and millions of dollars to unearth. They are not simply symbolic nor recreational (no matter how much fun it is to plug in what you imagine Taylor Swift’s current deal with UMG resembles), but rather pragmatic support systems helping to demystify information that can quite literally change the course of careers.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW PUBLISHING SIMULATOR

Definitions

Because the types of income, deal terms, and language typical of publishing are less commonly discussed than those in record deals, it feels more crucial to outline some of the key terms you’ll see on the publishing simulator. For a fuller look at some key terms you’ll encounter if you work in music in any commercial capacity, Adam Bainbridge (indie artist Kindness) put together this very helpful glossary of some important, common ones (and did it in Notion, no less, the tool I use to organize my life). For a publishing-specific set of terms, I’ve written the below:

Songwriter / Composer - A songwriter or composer is any person who contributes to melodic and/or lyrical composition of a song. It is crucial to note that a songwriter =/= lyricist; lyricists are songwriters, but songwriters can also be people who compose melodic elements (or any elements a group of collaborators deem worthy of songwriting credit) without contributing lyrics. Understanding this distinction can help in understanding why, for example, the list of songwriters on a Kanye West song can look like an endless enumeration of Biblical names—if a song embodies a sample and has multiple contributors who all derive publishing (or were given publishing percentages), all the songwriters on the sampled song are technically songwriters on the new song.

Lyricist - The person who writes the lyrics.

Composition - The melody and/or lyrics that make up a song; the composition is the copyrightable material that is embodied in a sound recording (or master recording).

Mechanical royalty - A publishing royalty derived from a song every time that song is reproduced, whether in a physical form (on a CD, tape, vinyl record, etc.) or in a digital form. The statutory rate for these royalties is 9.1¢ for songs on physical recordings (and permanent digital downloads like iTunes or Bandcamp).

Digital mechanical royalty - The streaming version of mechanical royalties. No statutory rate governs these payouts (DSPs negotiate directly with publishers).

Performance royalty - Royalties paid to songwriters for the public performance of a song (radio broadcast, live performance, TV broadcast, restaurants, bars, supermarkets)

Digital performance royalty - Royalties for non-interactive streams.

Co-publishing deal - A deal in which a songwriter assigns ownership of their catalog (for a contractually agreed upon period) to a publisher; a typical co-publishing deal also comes with the promise of creative services (A&R to help set up collaborations between songwriters, producers, and artists and also place full songs and beats with artists looking for either) and synchronization services (a team of representatives who pitch music for placement in films, TV shows, video games, etc.).

Administration deal - A deal that assigns a music publisher to administer the rights to a songwriter’s catalog and collect royalties on their behalf for a prescribed period of time. In an administration deal, the songwriter retains ownership of their rights.

Writer’s share - Half of the income generated by a performance royalty. The writer’s share goes directly to the songwriter, unless someone has purchased this stream of income.

Publisher’s share - The other half of income generated by a performance royalty. This is the share of revenue typically assigned to a publishing company or administrator. Until a songwriter does a deal with a publisher or administrator, they retain both the writer and publisher’s shares of their portion of any song they write.

Metadata - The dictionary definition of metadata is “noun - a set of data that describes and gives information about other data.” Thrilling. In practice, in music, metadata covers everything from a songs title, artist name, and writers/composers, to its BPM, key, and length, and on to the more complex circumstances governed by contracts—who owns what, who gets a percentage of what when money comes in from different sources, how long these arrangements last. Metadata is absolutely crucial to the proper monetization of music. There are no fewer than 88 distinct metadata points that govern proper payment.

Split - The portion of a song that a songwriter has contributed. There are numerous conventions and schools of thought for determining a song’s splits. Some adhere to the notion of “bodies in a room,” i.e. splitting the song evenly based on the number of songwriters present for its creation (common in Nashville and pop music). Some adhere to the notion of a “track and topline” split, separating the lyrics / vocals and the underlying soundbed (the track) into two discrete halves that can then be divided further among the collaborators on each side (common in hip-hop, R&B, and pop). A songwriter’s contributions to a song can be represented in a number of ways, largely rooted in whatever is agreeable to the collective writers on a song.

Split sheet - A document that outlines the publishing splits for the songwriters on a given song. Split sheets can be filled out on their own, but are also often included as a part of contracts between artists and their collaborators on songs.

The Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC) -From the MLC’s website: “The Mechanical Licensing Collective (The MLC) is a nonprofit organization designated by the U.S. Copyright Office pursuant to the historic Music Modernization Act of 2018. In January 2021, The MLC began administering blanket mechanical licenses to eligible streaming and download services (digital service providers or DSPs) in the United States. The MLC will then collect the royalties due under those licenses from the DSPs and pay songwriters, composers, lyricists, and music publishers. The MLC has built a publicly accessible musical works database, as well as a portal that creators and music publishers can use to submit and maintain their musical works data. These tools will help ensure that creators and music publishers are paid properly.”

Performance Rights Organization (PRO) - A performance rights organization (also known as a performing rights society) primarily serves to collect and distribute royalties on behalf of songwriters and publishers.