“Numbers on the Board” is a monthly column inspired by Walt Hickey’s Numlock News, adapting that format for the music business. A dive into the numbers headlining and defining stories of interest.

One note on this month’s edition of Numbers on the Board. I’m keeping it a bit brief as I’m preparing a longer essay on the current state of copyright for next week.

Grammy’s Round Up

With the annual Grammy announcement coming early in November, there were bound to be a few fun numbers to dive into. And so we shall.

28.5 - Average age of best new artist

Since the dawn of time, philosophers the world over have pondered a question seemingly without answer: How the fuck do the Grammy’s define “Best New Artist?” There are many years in which the category is packed with numerous contestants in their thirties, singers, rappers, and musicians who’ve dropped multiple albums across many years. 2025’s Grammy’s will be no different.

The average age of the artists in the category is 28.5 (30 if you break Khruangbin into its constituent members. Sabrina Carpenter (25) has released six albums. Khruangbin (Laura Lee Ochoa, 38, Mark Speer, 45, and DJ Johnson, age unknown from my cursory online search) has released five. Shaboozey (29), Raye (27), and Chappell Roan (26) have both been dropped by major labels. Shaboozey found success as an “independent” artist with distribution powerhouse Empire. Raye had a similar arc, her biggest hits coming after being jettisoned by a major and signing with “independent” distributor Human Re Sources (owned by Sony). Chappell Roan got dropped by Atlantic before finding success with UMG-owned Island Records. I hear Teddy Swims’ voice and assume he has been on the earth for something like 100 years. His listed age is 32, but like a kid in the Little League World Series who’s a head taller than everyone else, I’m going to guess he has the vocal chords of a 40 year old.

The two artists who truly seem to embody the nebulous idea of newness profferred by the Recording Academy are Benson Boone, 22, and Doechii, 26.

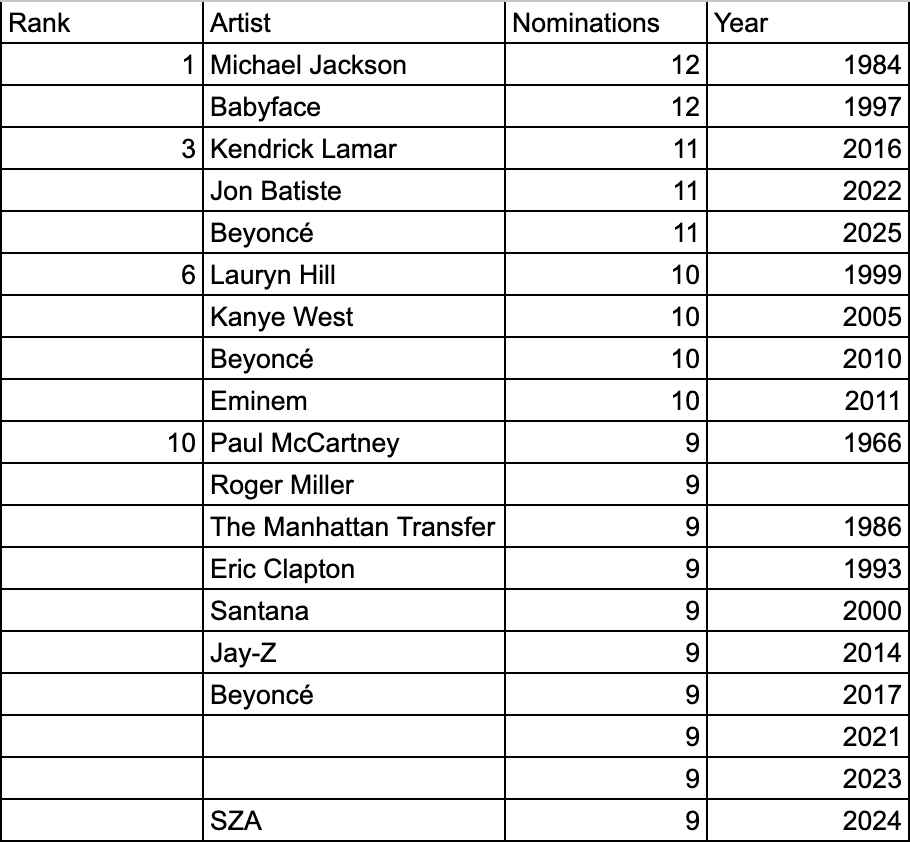

11 - Number of Beyonce nominations this year

On November 8th, Beyonce became the most nominated female artist in a single year in Grammy history. The second most nominated artist overall in a single year, tied with Kendrick Lamar in 2016 and Jon Batiste in 2022. Beyonce’s 2025 stands behind only Michael Jackson in 1982 and Babyface in 1997, with each of the latter two nominated for 12 Grammy’s in their respective years. She is also the third most nominated artist in a single night with 10 (tied with Lauryn Hill, Kanye West, and Eminem), and fourth most nominated in a single night with 9 (a feat she achieved three times; tied with Paul McCartney, Roger Miller, The Manhattan Transfer, Eric Clapton, Santana, Jay-Z, and SZA).

Overall, Beyonce has been nominated for 99 Grammy’s, winning 32. Both of those figures are records. An early prediction: Beyonce will win two more awards, padding her already gaudy stats, but will lose in the three of the big four categories in which she is nominated (Album of the Year, Record of the Year, Song of the Year). A Grammy tradition as old as Beyonce’s career (and a shame, as Cowboy Carter was easily one of the most played and beloved albums in my household this year until my son decided that we were only allowed to listen to whatever he wanted to listen to sometime around his second birthday).

Most Grammy nominations

Worth noting that Billie Eilish has 32 nominations and nine wins currently, and feels like the young artist with the best chance to one day surpass Beyonce’s statistics (though we should never count out Taylor Swift either).

Most Grammy nominations in a single night

Most Grammy wins

One new Producer of the Year winner

For the first time in five years, Jack Antonoff is not nominated for Producer of the Year. That means for the first time in three years, Jack Antonoff won’t win Producer of the Year. Not only will this year’s winner break that streak, they’ll also be a first time recipient of the award. While Dernst “D’Mile” Emile II and Dan Nigro have been nominated prior to (three times and two times, respectively), Alissia, Ian Fitchuck, and Mustard are all first time nominees. Nigro is the frontrunner and likely winner, though D’Mile is easily one of the best producers of this generation and deserves the award at some point, if not this year. If Mustard somehow wins, it is because the sheer force of “Not Like Us” lifted him up.

$212 billion - the music industry’s annual economic impact in the US

With all this success and rampant growth in the air, it feels challenging to understand how so many jobs could be getting slashed. When you’ve maxed out infinite growth on fundamentals, the natural progression is to “trim the fat,” eliminate jobs and jettison the salaries that come with them.

There have been no fewer than six corporate restructurings at the major label level this year, with UMG, Sony, and Warner, re-enacting the Red Wedding at least twice each (that I know of), rounds of layoffs accompanied by messaging about new leadership, visions of the future, and, more importantly, visions of soaring stock prices. All of this corporate flesh cutting is harder to stomach when you encounter reports like the RIAA’s recent study that the music industry has an annual economic impact on the United States of $212 billion. While that figure is obviously spread across a great many verticals, adjacent businesses, and human beings, it does not reflect an industry in a state of free fall, or even one in a state of profound existential crisis. It reflects a healthy ecosystem, one far from the depths of the early 2000s.

A few other figures point to the industry’s overall wellbeing. Per an annual report by PRS Chief Economist Will Page, the value of musical copyright worldwide rose to $45.5b in 2023, up 11% from the previous year (and up from $25b, the figure Page noted when he began reporting in 2014; it bears mentioning that that would be around $40b adjusted for inflation). While relative figures tell us little about absolute returns, it seems symbolic that music copyright has now surpassed the value of the global film box office.

While Page doesn’t provide granular detail on the biggest winners of the current windfall, he does note 63% of the global value being captured by record labels and artists, with the remaining 37% going to songwriters, publishers, and their collective management organizations (CMO’s). These figures don’t give much insight into the state of the individual artist, songwriter, or producer, but taken in conjunction with Luminate’s mid-year report (which I dissected in part here), a picture of a future in which “independent” artists are capturing a greater percentage of the pie starts to take shape.

Within this growth, we also see the continued rise of vinyl. Per Fast Company: “In 2023, U.S. revenues from vinyl records grew 10% to $1.4 billion, the 17th-straight year of growth, according to the Recording Industry Association of America. Records accounted for 71% of revenues from non-digital music formats, and for the second time since 1987, vinyl outpaced CDs in total sold.”

No matter the difficulties mounting due to AI, pandemics, and any number of new challenges, no matter how difficult the business of running a major or indie label has become, it is still hard to fathom the human toll of lost jobs when the industry clearly brings so much economic health to areas it touches.

$500m - UMG sues TuneCore and Believe

I heard rumblings that Universal Music Group’s next big move in a year of corporate restructuring and aggressive partnerships would be targeting distribution companies piping thousands of bootlegged releases from UMG artists onto DSPs. On November 4th, UMG and two of its largest distributed labels (ABKCO and Concord Music Group) sued Tunecore and its parent company Believe Digital, accusing one of the world’s most popular independent distributors of industrial scale copyright infringement.

What I find most fascinating about this suit is that it accuses Believe of being “‘fully aware that its business model is fueled by rampant piracy’ in ‘pursuit of rapid growth,’ essentially accusing both parent and subsidiary companies of intentional copyright infringement. Years ago, companies like Facebook and YouTube essentially abdicated responsibility for copyrighted material uploaded to their platforms, instituting some level of content ID and copyright control though ultimately pushing liability onto the individual uploader. At the heart of UMG’s TuneCore/Believe lawsuit lies the idea that the responsibility is not just on the individual uploader, but on the distributor as well. UMG’s lawyers take it a step further, claiming Believe willfully engages in fraudulent claims on copyrighted materials, delayed payment of royalties to their rightful payees, a repetitive distribution of infringing songs after claims have seemingly been resolved. Though a distribution company or label has a legal responsibility not to disseminate copyrighted material without contractual proof that an individual has the right to commercially release a work, companies like TuneCore, which allows any user to upload music to all DSPs for a low set fee, have hundreds of thousands of users releasing millions of songs annually. Even if we assume best intentions on the part of TuneCore and Believe, it is almost impossible to effectively police individuals looking to profit off infringement. While aspects of UMG’s claim may certainly be legitimate, I imagine the reality constitutes a blend of violations via willful allowance and unintentional facilitation.

This problem is also not novel. When I was an intern at Motown in 2010, I remember scanning the iTunes charts and finding fraudulent releases by “Kayne West” charting in the run up to the release of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. UMG didn’t sue Apple then, but I imagine TuneCore and Believe make for more vulnerable targets.

906 days - the time from Young Thug’s arrest to his freedom

When Young Thug got arrested and charged as a part of a racketeering case in May 2022, it felt like another in a growing spate of lawsuits meant to make an example of rappers whose music portrayed criminal pasts. On Nov 9, 2023, over a year into the proceedings, Judge Ural Glanville ruled that seventeen sets of lyrics could be admissible as evidence in the case and were not protected by the First Amendment. Glanville said: “[Prosecutors are not] prosecuting your clients because of the songs they wrote. They’re using the songs to prove other things your clients may have been involved in. I don’t think it’s an attack on free speech.” I would politely disagree with Judge Glanville, but, of course, I’m just a guy who took the LSAT twice and not an actual lawyer.

At the time, it did not seem a likely candidate to become the longest criminal case in Georgia history, a multi-year saga that spawned numerous, bizarre court room moments, high profile snitching accusations, and one inescapable Gunna hit. Billboard has a detailed timeline of the trial’s twists and turns.