Numbers on the Board (May 2024)

A look at the numbers defining the music news of the past month.

“Numbers on the Board” is a monthly column inspired by Walt Hickey’s Numlock News, adapting that format for the music business. A dive into the numbers headlining and defining stories of interest.

10 songs, several hundred million streams, two Billboard #1’s - Kendrick Lamar vs. Drake

Unless you somehow managed to avoid the internet or the men in your life for the past month and a half, you probably have consumed far too many memes, articles, and musical artifacts from the beef of the century, Kendrick vs. Drake.

I am not going to illuminate the personal context of the songs themselves, nor am I going to comment on the “quality” of the beef. While watching two superstar rappers spar so brutally plays for modern gladiatorial spectacle, Pitchfork’s Alphonse Pierre captures much of my personal feeling about the situation’s grotesquery and downright oddity. We are talking about two titans battling. A Pulitzer Prize winner. A rapper with more number ones than the biggest pop star ever and more streams than any artist, period. By any measure two of the defining artists of their generation, a window that now stretches 15 years for the both of them. This sort of conflict breeds the natural, morbid excitement of any rubbernecked disaster, but when songs take a decidedly sinister tone and people start opening fire on someone’s home, combat sport may have metastasized into pure dark.

Value judgments aside, I found a few absolute aspects of the beef fascinating.

First, it produced a staggering volume of music in a brief window. Here’s a timeline:

Future and Metro Boomin ft. Kendrick Lamar - “Like That” (March 22, 2024)

Drake - “Push Ups” (April 13, 2024)

Drake - “Taylor Made Freestyle” April 19, 2024)

Kendrick Lamar - “Euphoria” (April 30, 2024)

Kendrick Lamar - “6:16 in LA” (May 3, 2024)

Drake - “Family Matters” (May 3, 2024)

Kendrick Lamar - “Meet the Grahams” (May 4, 2024) [Ed. Note: Both “Family Matters” and “Meet the Grahams” came out while I was watching Challengers in a theater, which accidentally combined multiple zeitgeist-y moments into one]

Kendrick Lamar - “Not Like Us” (May 4, 2024)

Drake - “The Heart Part 6” (May 5, 2024)

Sexyy Red ft. Drake - “U MY EVERYTHING” (May 24, 2024)

That’s 10 songs including features and non-DSP drops.

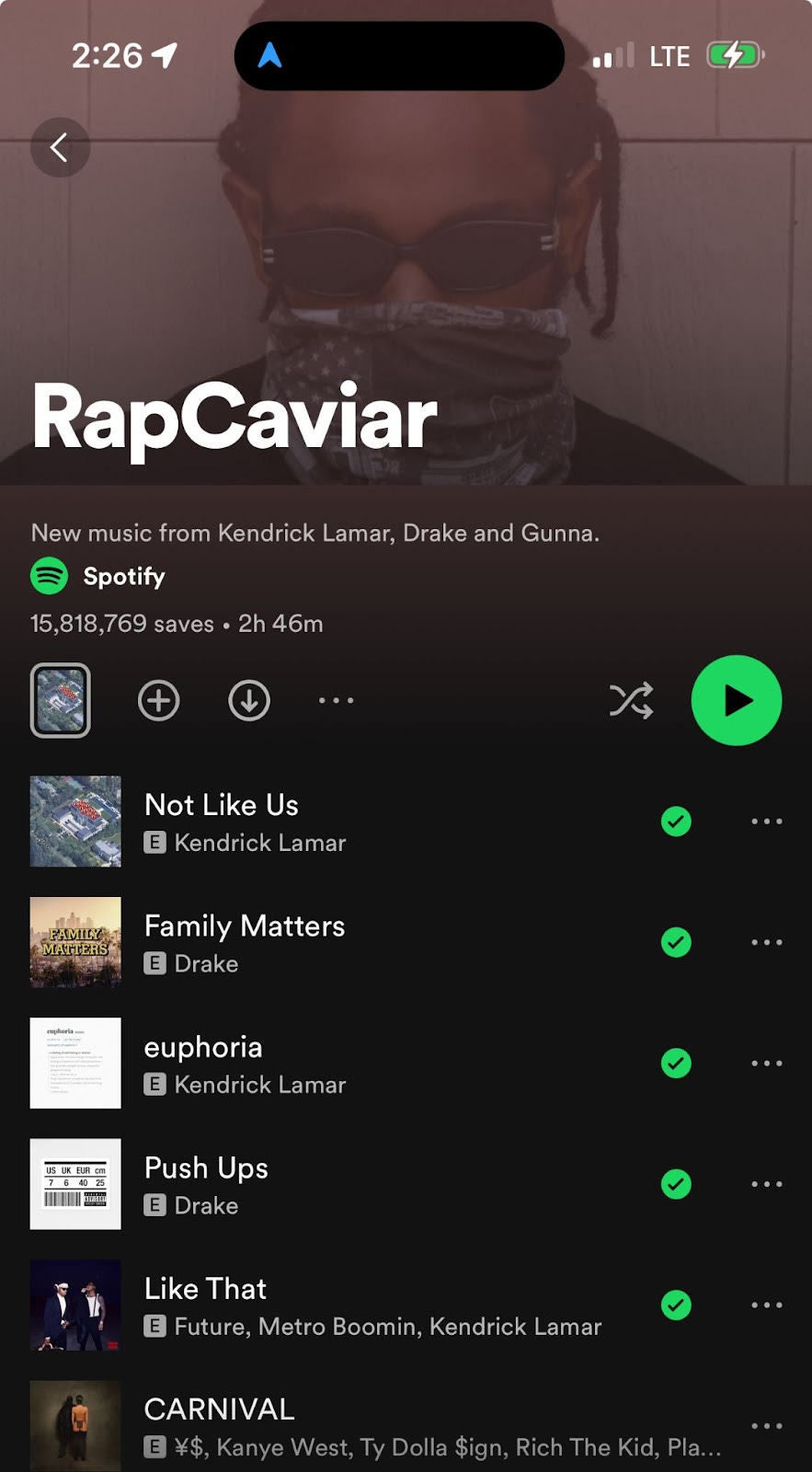

Second, this is the first rap beef to launch multiple measurable hit records. It is as much a statement of technological change as a reflection of the songs themselves. The tent pole songs of the battle have generated several hundred million streams. “Not Like Us,” “Euphoria,” “Family Matters,” and “Push Ups” all charted on Billboard, weeks after “Like That” opened the floodgates withs its debut at number one. . Close to the battle’s peak in early May, this is what Spotify’s Rap Caviar looked like:

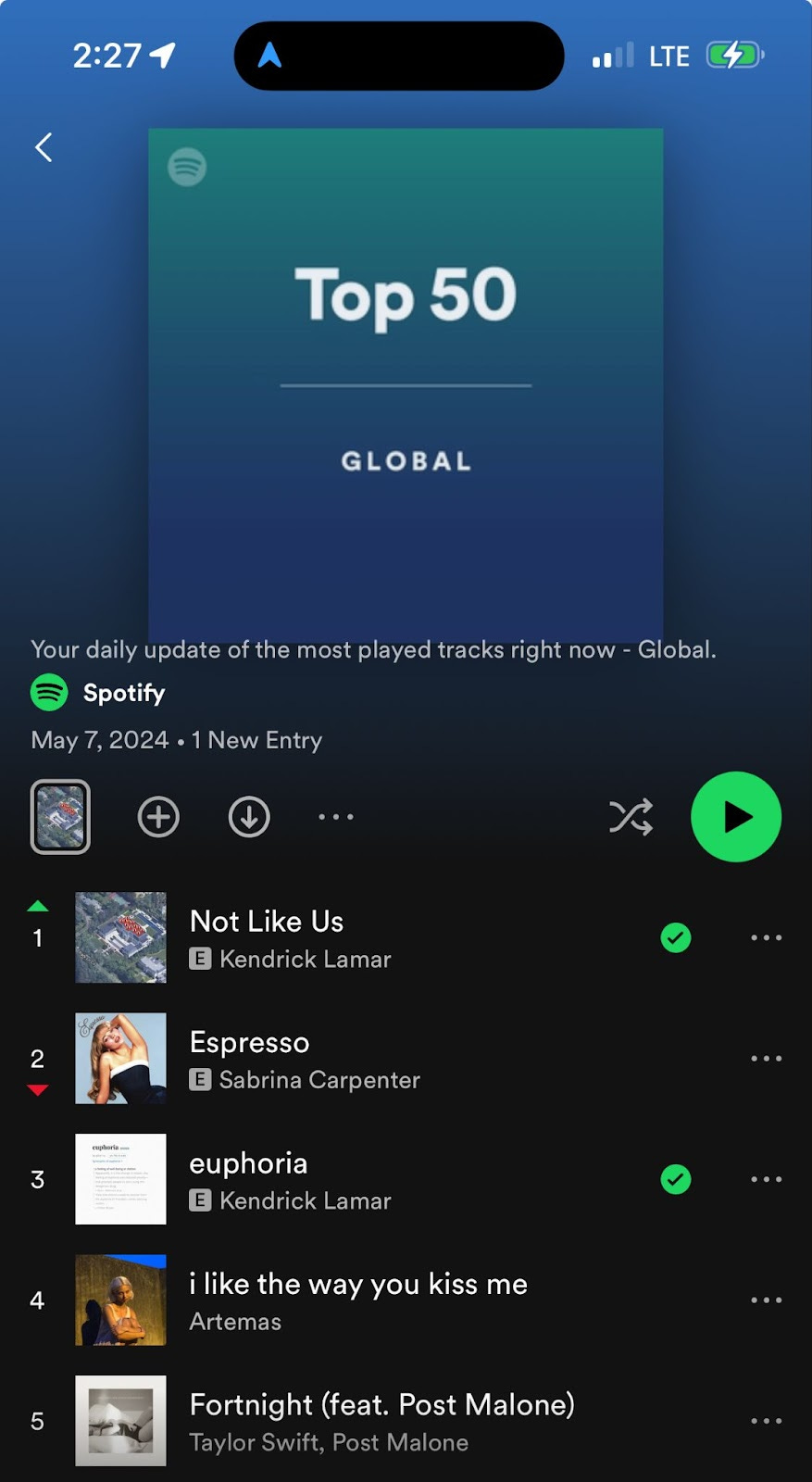

And below was the Global Top 50 on May 7:

Today, “Not Like Us” is #4 on the Spotify Global Top 50 and stands at 240m streams on Spotify alone. Both “Not Like Us” and “Push Ups” found their way onto Today’s Top Hits, which would be something like “Takeover” and “Ether” having videos and being on TRL at the same time in 2001/2002. Though Megan Thee Stallion had a #1 with a diss record earlier this year (“HISS”), it fell off the charts the following week. “Not Like Us” seems poised to be one of the defining songs of the summer if not the song of the summer, breaking the record for the fastest rap song to 100m streams (a record previously held, naturally, by Drake’s “God’s Plan”) on its way to a Billboard #1 debut.

“Not Like Us” specifically addresses Drake, but its generalized “us vs. them” chorus and addictive Mustard beat give it the sort of broad anthemic appeal that translates to clubs and arenas. It rallies the bonded “us” against whomever “they” are. In this way, “Not Like Us” has a chance to live beyond the beef. It may not reach the dictionary definition status of a song like “Ether” (whose title, as many have reminded us over the past weeks, fast became a synonym for beating an opponent in battle), but it has proven to be a hit on its own merit as much as a hit launched into orbit by the g force of the beef.

Hip-hop history holds countless classic diss records that come up in conversation any time a beef boils over. Though often sending shock waves through culture and time, few made broad commercial impact. Many more never saw official release, popping up on mixtapes or as digital downloads. Jay Z’s “Takeover,” Nas’ “Ether,” 2Pac’s “Hit ‘Em Up,” Ice Cube’s “No Vaseline,” Boogie Down Productions’ “The Bridge is Over,” Pusha T’s “The Story of Adidon,” even Drake’s own “Back to Back'' didn't balloon into broader public consciousness in the manner of “Not Like Us.” Here again, it is difficult to divine the power of the record itself from the might of streaming and social technologies that helped make “Not Like Us” feel omnipresent from the moment it was released.

In its rapid escalation, the beef also illustrated the entanglement of hit songs and metanarratives in our current moment. When Kendrick released “Meet the Grahams” and “Not Like Us” in fast succession, he found Drake flat-footed, exuberant, certain he’d won after releasing the searing “Family Matters” (itself a response to Kendrick’s “Euphoria” from earlier in the week and “6:16 in LA” mere hours prior). 48 hours later, Kendrick had turned the tides by delivering an immediate hit (“Not Like Us”) hours after striking a chilling tone reserved for the most disturbing pantheon of disses (“Meet the Grahams”). To add insult to injury, the viral explosion of Metro Boomin’s “BBL Drizzy” competition underscored the asymmetry of this battle (also making this beef the first to feature a crowd-sourced campaign against one of the combatants). A torrent of memes followed, all targeting various soft spots exposed by Kendrick. Drake typically unleashes these sorts of attacks. He doesn’t weather them. The barrage raised salacious questions about both stars (many of which have failed to be substantiated with concrete answers), turning accusations into rallying cries across Twitter chatter and the charts.

In the past decade, Beyonce and Taylor Swift have largely perfected the craft of story-sewing into public discourse. The rollouts for their respective recent albums COWBOY CARTER and The Tortured Poets Department rolled out via multimedia conversations as focused on the personal and social implications of these creations as the music itself. Though the former’s “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” is a hit by any measure, the discourse Beyonce stoked around the definition of country music strikes harder than any chord played across COWBOY CARTER. Is “Not Like Us” a hit on its own merit? Though unknowable, the answer is likely no (though it sounds like a hit, whatever that means). Would “Like That” have been a number one record without the Kendrick verse that turned a cold war into a hot one? As a non-single towards the middle of an album, not likely. Is all of this compelling primarily as melodrama? Possibly!

A final, tangential point: I am glad that “Like That” catapulted Eazy E’s “Eazy-Duz-It” sample back into the ears of the listening majority. For my money, the best use of this sample remains Three 6 Mafia’s “Ridin Spinners.” Bafflingly, there is another pretty famous interpolation in “Like That” that seems to have evaded crate digging YouTube channels and sample websites alike. No, I will not tell.

If you want the entire history of the beef in every explicit and subliminal detail, someone put together all the songs in question sequentially in one 43 song playlist. “Enjoy” might be the wrong word, but it is available if you want to relive it all.

10 songs per second - the number of songs generated on Udio right now

Whatever you think the music business will become in the AI age, I can assure you it will likely be messier and probably weirder.

This month, Music Business Worldwide reported that users are making 10 songs per second on generative AI music tool Udio, one of a number of startups that have fallen under suspicion for potentially using copyrighted material to train their model, something we in the industry call “a big no no.”

In the background, similarly scrutinized generative AI audio startup Suno announced a $125 million dollar raise at a $500 million valuation. It is unclear how much of that money will be earmarked for legal bills and copyright clearances. Judging by the recent, bellicose stance taken by Sony Music against anyone illegally using their catalog for model-training, companies like Suno and Udio employing gray practices may soon find themselves dragged into similarly costly litigation and the overhang of moral issues currently besetting OpenAI and Anthropic.

Amidst all this back and forth about the future of creation, Chinese megalith Tencent announced in its latest annual report that it has developed an AI-powered predictive model (“PDM”). Quoting the report:

“Using the proprietary deep learning content value assessment algorithms, the PDM is capable of predicting the next hit song by analyzing recent popular music trends and user preferences for precise content discovery and distribution to interested users.”

While that may be a feint to boost investor confidence in Tencent’s ability to shape the future of consumer habits in a volatile time, it is also an obviously desired end state for the majority of major media companies. Combined with the sheer volume of music being created and distributed, the announcement of powerful artistic sabermetrics makes adds to the particularly daunting conditions of this time for any artist looking to attain conventional commercial success.

Still in all, I believe this to be one of the most exciting times in the history of creation. More tools are available for artists, producers, and songwriters to make and promote music than ever before. Fewer barriers exist between creator and audience. Anyone with the slightest curiosity can explore nearly the entire history of music with relative ease. Creation forms the new consumption as old habits (music as a medium of social exchange and interaction) find new expression through technologies from DAWs to games to generative models to social platforms that expedite production and connect creators as never before.

If you feel all the above constitutes an unequivocally grim state of affairs, there may be hope for you in observing millennia of human behavior. All these macro trends will produce opposite reactions, pushing many fans and consumers to seek out artists who tell stories, who have more traditional creative profiles, and who implicitly or explicitly shun the onslaught of commercialized tech tools (though not a one-to-one comparison, we have seen a shining example of counter-programming and measured risk-taking in the storied rise of A24). History has proven enough times that you can’t beat tech unleashed without guardrails. You certainly can’t erase an idea once it's spent a second in someone’s mind, but it also feels like pieces painting the rise of AI music as an inevitable human labor and creativity displacer fails to account for human behavior and narrative thinking. Humans seek the path of least resistance often. We also seek individuation, in part through creativity and consumable expression. I don’t think thousands of years of human behavioral history and imagination will crumble simply because I was able to conjure a funny fake Kendrick Lamar diss out of Udio.

One thing that is certain: Our current copyright regime will buckle in a new reality that sees thousands of pieces of music generated daily based on the DNA of decades of commercially released music, all or some of which may not have been licensed for the purpose of training large models. I scratched the surface of this topic last May, but I plan to dive deeper in the coming months.

91 days - Time between UMG’s deal with TikTok expiring and a new deal

Here’s a list of notable labor strikes in sports and entertainment:

2021-22 MLB lockout: 99 days

2007-2008 WGA strike: 99 days

1941 Disney Animators strike: 115 days

2023 SAG-AFTRA strike: 118 days

2023 WGA strike: 148 days

1960 WGA strike: 148 days

1988 WGA strike: 153 days

2011 NBA lockout: 161 days

1998-99 NBA lockout: 204 days

1994-95 MLB lockout: 232 days

1942–44 AFM strike: 834 days

What they all have in common: each lasted longer than the 91 days separating the expiration of Universal Music Group’s license agreement with TikTok and the announcement of a new deal. While neither a strike or labor stoppage, UMG removing its catalog from the world’s most popular social promotion platform constitutes the one of the only acts we’ve seen in music over the past 80+ years that remotely resembles anything like labor solidarity or collective bargaining at this scale. Typically, we’re only treated to individual protests by superstars like Taylor Swift (who kept her catalog off of Spotify for almost three years from November 2014 to June 2017) or aging ideologues like Neil Young (who kept his music off of Spotify for two years in an ultimately limp protest of the platform’s mega deal with Joe Rogan) and Joni Mitchell (who both joined Young in protest of Rogan and followed him back onto Spotify shortly after he decided to return his music to the streamer).

When the WGA strike happened last year, there were a few articles about the reasons why similar labor stoppages and negotiations take place in music. The answer, inevitably, landed on a simple truth: The music industry doesn’t possess a union of comparable strength, capacity, or purpose. The reasons for that absence are at once nebulous and completely clear. On the one hand, the 1942-44 AFM strike spurred congress to set restrictive, confusing limits on the ways in which musicians, performers, and songwriters could collectively bargain. At the same time (and perhaps, in part, because of this legal labyrinth), the individual artist, musician, songwriter, and producer has become increasingly interchangeable over time. The same is less true in, say, the NBA, where the Players Association owes its relative strength to the fact that removing the 30-40 best players from the game would drastically undermine the final product. Fans know it. Media outlets know it. Players know it. Owners know it. Whatever lip service label execs pay to “career” or “true” artists, the modern record business nods implicitly to the fungibility of hits.

A passage from TikTok’s 70 page lawsuit against the United States reveals the way the company views its relationship to musical IP by omission:

“TikTok is an online video entertainment platform designed to provide a creative and entertaining forum for users to express themselves and make connections with others over the Internet. More than 170 million Americans use TikTok every month, to learn about and share information on a range of topics — from entertainment, to religion, to politics. Content creators use the TikTok platform to express their opinions, discuss their political views, support their preferred political candidates, and speak out on today’s many pressing issues, all to a global audience of more than 1 billion users. Many creators also use the platform to post product reviews, business reviews, and travel information and reviews.” (p. 7-8)

Notice no mention of the music industry or even of music period. While TikTok has become absolutely paramount to modern music promotion, it does not seem as if music is reciprocally important to TikTok’s continued success (or its view of itself). That leads me to believe the next contractual dispute between TikTok and a major label group might make 91 days seem comparatively short.

$1.572B - Hipgnosis sale continued

Speaking of IP funnels that were supposed to create more leverage for songwriters (or at least for the entities that owned their rights), the public poker game for Hipgnosis has ended. One time frontrunner Concord officially pulled out of the bidding on May 16th, ceding pole position to Blackstone. While Blackstone’s $1.572 billion bid still needs to pass a shareholder vote in July, its acceptance seems all but a foregone conclusion. It is fitting that the company most famous for popularizing the catalog mega deal will meet its “end” at the hands of the trillion dollar investment giant that helped fund its start, only some six years later.

“a couple thousand” - The number of albums Steve Albini produced

“Albini estimated he’d recorded ‘a couple thousand’ albums in a 2018 interview; his productivity was related to the purity of his process. Albini sessions were done quickly and affordably. Instruments were recorded with room microphones to capture the natural reverberations of the space. Analog gear and one-take recordings were preferred. ‘Anyone who has made records for more than a very short period will recognize that trying to manipulate a sound after it has been recorded is never as effective as when it’s recorded correctly in the first place,’ he told Sound on Sound magazine.” - Christopher R. Weingarten, “Steve Albini’s 10 Essential Recordings” (New York Times)

Legendary rock producer and engineer Steve Albini died on May 7, 2024. At 61, he was still active, still performing with his band Shellac, still inspiring new generations of artists, producers, engineers, and executives searching for some sort of truth in creation, refusing to accept the status quo proffered by trade magazines, sound bites, and social media clips. His 1993 invective “The Problem with Music” remains as gutting, incisive, and accurate as it must have felt when first published, a north star for anyone who always felt the music business might be pretty fucked up, but didn’t have the back of the envelope math or anecdotes to prove it.

Albini considered himself more engineer than producer. He saw his role more as a recorder of the present than an embellisher of the absent. His self-effacing style made him a go-to for bands seeking purity of energetic capture. In my decidedly limited ability to appraise rock, I have always found “Heart Shaped Box,” the iconic single from Nirvana’s Albini-produced album In Utero, to be the perfect monument to this approach, timeless and hair-raising.

Albini’s output is staggering and well worth exploring. No doubt others are more suited to eulogize him than I am and already have, but I would be remiss if I did not pay respects to a titan that followed his own compass.