“A city is not the sum of all the people in it, and it’s not the sum of all the roads and all the buildings. It’s not the sum of all the events that take place in it. There’s something much more than that; it’s some integration of all those. And it’s useful as a concept to think of it as some collective phenomenon and talk about its own individuality. And we do, obviously, talk about New York and San Francisco, and so on. It does have a sense of individuality….And so you come to this concept, which is inherently the idea of complexity and complex systems. Yes, it is made of constituents. But if we start to delineate them, it’s almost an infinite number and associated with them is an infinite number of equations.”

- Geoffrey West, 2017 interview (as reprinted in A Sommelier’s Atlas of Taste by Rajat Parr and Jordan Mackay)

From CreateSafe’s start, simplification and user autonomy have guided our product philosophy. In 2017, imagined tools that streamlined metadata management. Early prototypes evolved into the Record and Publishing Simulators—radical illustrations of how deals work in music. Our simple Rights Visualizer distilled IP contracts, eliminating confusing fluff. Our goal has been lofty, but singular: Build the operating system for the new music business.

We’re now introducing Droplink to streamline the sharing of music and fix the fragmented digital link between artist and audience.

The TL;DR version: Droplink is a listening tool that connects artists and fans. It replaces “pre-save” links, typically useless after release day. Droplink allows artists to set quests for their users, empowering creators to own the data generated by their music and build lasting bonds with their audience. Droplink is a leap forward in fusing distribution, communication, and consumption.

We launched the first Droplink campaign with Nas’ King’s Disease III. As well, you can see the product in action below for an upcoming Grimes campaign.

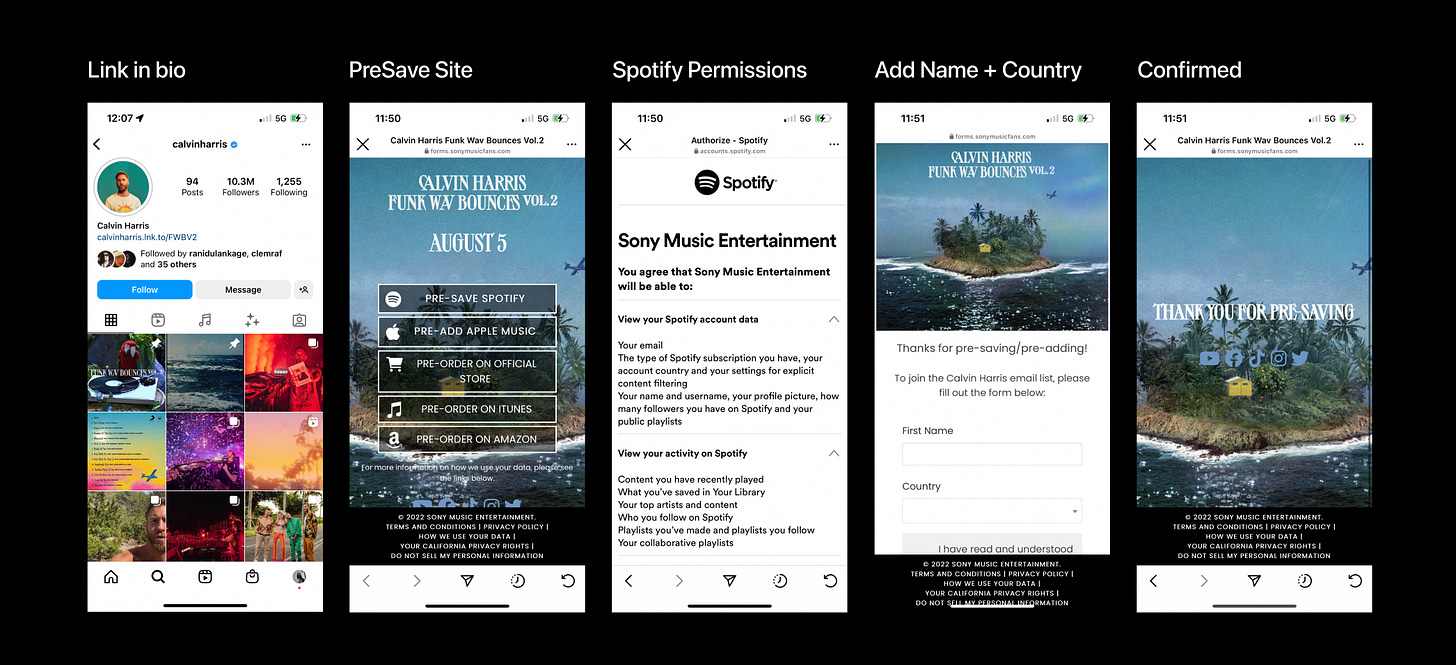

If you follow your favorite artists on social platforms, they (or whoever operates their Twitter and Instagram accounts) have likely called on you, beloved fan, to “pre-save” their new single or album. Pre-saving has become de rigeur for rollouts, a checklist item labels and distributors sternly recommend. In theory, strong pre-save activity shows DSPs that breathing human beings care about an artist’s music. In practice, the results of pre-save campaigns often fade into a post-release haze of quasi-insights, muffled by the incessant siren’s call to keep releasing music as you chase the lottery ticket that lands you atop the charts.

The main problem: Pre-saving doesn’t actually work as intended. It’s a directive from artist to audience that is often broken at the DSP level and, most importantly, doesn’t allow true interaction with fans. It is a broadcast command that permits no real response.

Distributors and labels will tell you pre-saving spurs algorithmic playlisting on Spotify (Release Radar, Discover Weekly, radio). Seems logical enough, though the exact recipe is hard to divine: Some alchemical combination of saves, adds to user-generated playlists, associated artists, user follows of an artist, external links driving people to Spotify, and internal playlist pitching through the Spotify For Artists app. Apple has always been guarded with this sort of data cocktail and boasts a more humanistic editorial approach than Spotify’s increasingly machine-learned feedback loop.

For artists and fans, five major problems arise from the pre-save/pre-add process:

Fans receive nothing in return. Pre-saves don’t give fans much more than the solace of knowing they have potentially made an offering at the altar of the algorithmic gods governing their favorite artist’s DSP success. Most fans likely don’t feel compelled to pre-save because they’ll be listening to anticipated new releases on the day they come out or shortly thereafter; pre-saving seems a superfluous step. There is also no promise that a fan will be acknowledged for their action.

The process is cumbersome and may require data permissions that feel invasive to the average fan.

Most pre-save links don’t work as intended. Links themselves don’t always properly save the song, leading fans to have to dig for what exactly got saved and where it got saved within their DSP library (a problem endemic to Spotify, explained in depth by our very own Lyrah). Worse yet, by driving likes/saves on Spotify, pre-saves can sometimes raise alarms that a user is attempting to game the algorithm.

Once pre-saving is done, the pre-save link becomes digital debris. It is dead weight in the Internet slipstream, never inspiring another visit from a fan. The process begins again with each release, with no mechanism for continuity.

Artists don’t own demographic data. These interactions have the power to generate valuable demographic data for the large corporations providing the infrastructure, but not the artists whose art drives the interactions. This data has been publicly treated like runoff for years, served back to artists and their teams in obfuscated forms at best. Artists could gain greater insight into their audience from a moment that signals intent. Instead, they walk away with little better understanding of the context surrounding this action. In an age when numbers increasingly tell less of the story, artists need a better understanding of how and why listeners are engaging with their music.

Droplink is a better, cleaner way to run campaigns around releases. It opens up new possibilities by centering listening, communication, and user rewards, rather than the unilateral request to save a song or album.

With Droplink, artists can:

Set up pre-saves that drive actual listening activity, rather than just pumping likes (as some platforms may view a greater ratio of likes to listens upon release as indicative of attempts to game the algorithm).

Collect email, phone number, and crypto wallet information from fans. Identify and engage with individual fans, rather than understanding fanbases only as opaque statistics. Learn about an audience as more than mere numbers, providing tools that help paint contextual pictures of an artist’s fans.

Directly notify fans when a song or album comes out, reminding them of the action they took in the first place. Message fans, directly sharing updates in the run-up to releases and after music comes out to create continuity between content drops.

Allow fans to connect existing crypto wallets for future rewards or create ad hoc wallets for fans who don’t already have them set up (or don’t want to connect their existing wallets). Crucial, as well, for fans who want rewards, but are not specifically interested in web3 as a mechanism.

Create content-driven quests and campaign pages with video and additional assets that energize the pre-save/post-release process. Present fans with post-release UGC campaigns that invite them to engage with released music in different ways (and could open the door for audience invention of interactivity and communication around music, as well as the development of game worlds bridging the digital and physical around musical IP).

Droplink enables network building through sharing and consuming music. It streamlines a fractured set of processes (pre-saving, fan engagement, demographic tracking) into a stylish, dead simple product that prioritizes listening—the actual experience of music—above pure like-farming and data mining.

Philosophically, two ideas outlined in Applied Science 7—data control and artist sovereignty—guide its purpose. With Droplink, artists and their teams can directly own the fan relationship, connecting with individual consumers and controlling all the data created by these interactions. [NOTE: CreateSafe does not hold exclusive access to fans’ phone numbers or demographic information. The artist receives and governs this information. Artists get direct insight into their audiences with limited intermediation—they don’t have to buy or beg for access to data generated by their art.]

Droplink considers music as entertainment, art, and medium of exchange. The current pre-save/pre-add system highlights music’s exchange value along a financial or transactional axis (driving commerce to an artist) and along an experiential one (an action promising the listener’s listening experience immediately upon release). Current processes fail to harness music’s power as a social medium, a favorite means of communicative exchange. We send songs to friends. We make playlists for family members or significant others. We buy records, in some cases for their audio fidelity, but often as superficial markers of our taste. We notch the passing of our lives with music. We swap records and digital files with one another if someone has a rare piece the other wants (even if that rarity only comes in the form of something being previously unknown to one friend or another). This mode of music as emotional causeway, music as aesthetic armor, music as social currency, and music as community fabric comprises much of its intangible value. These concepts have been hardest for the industry writ large to subsume into its commercial processes (the one genre that has truly figured this out, K-pop, has cultivated some of the most hardcore fanbases in music history).

In Applied Science 3, I wrote about the recording industry’s missed opportunity in the early 2000s. Major labels could have attempted to convert the obsessive pirates of sites like Oink’s Pink Palace into a dispersed archivist workforce, meticulously cataloging metadata in exchange for musical rewards (something members of these communities already showed willing to do). I also wrote how a South African genre and a simple chat app catalyzed a community:

“South Africa provides some interesting corollary possibilities from the last half decade. WhatsApp groups have become a hub for one of South Africa’s most electrifying dance genres, gqom. Users—artists, DJs, and fans—have created a kind of invite-only network for the sharing of MP3’s and information.”

KasiMP3, an idealistic South African startup conceived by Mokgethwa Mapaya, attempted to harness the kineticism of this blooming sound and fanbase with a novel model: Free uploads and downloads supported by ads, with ad revenue shared among artists. Built on the understanding that fans would pirate and share music they loved anyway, Mapaya reasoned “It is in our DNA as humans to communicate, especially to communicate the things we like, and in this ‘technology and innovation’ age, file sharing has become an extension of that communication.”

While Oink’s illegality undermined its potential and KasiMP3’s ambition outstripped its technology, the DNA of both platforms courses through any “___ to earn” model espoused: Find behaviors people already engage in readily; reward them for their engagement; develop community through quests that build members’ outward identities via repeated actions. As well, gqom’s prevalence on a “dark social” platform (WhatsApp) prefigured the surge of communities on Discord and Telegram, particularly the latter which seems to be taking hold for music sharing:

Droplink can be a campaign lodestone from the moment a song gets announced, hardcoding social meaning into an artist’s music. It provides a mechanism to send fans on quests that transform the call to pre-save into a valuable starting point, rather than a hollow end. Droplink’s data tools cut through the obfuscation of prevalent backends like Spotify For Artists, revealing flesh and blood fans so often reduced to vague numbers. Piercing this veil is the first step in forming real, bonded communities.

[As obtuse as it may seem, the Geoffrey West quote that opened this Applied Science speaks, in my mind, to the intricacies of fanbase building in an age of runaway complexity. You simply cannot cultivate lasting, dedicated fans if you only see “the city,” but do not attempt to understand the interactions of its constituent parts—and, at the same time, to understand that certain qualities of a fanbase will always remain irreducible, unable to be sketched by demographic studies.]

We are building on Droplink rapidly. Soon, it will enable artists to launch premiere-like experiences and listening parties, gathering friends and fans at specific times around pieces of content, inviting die-hards to connect with one another around the music and art they love. The full extent of what artists and their teams will do with Droplink remains to be seen; we’re excited to explore new paths for the creation of memorable moments. We see the pre-save as the beginning of an interaction rather than an endpoint. It should be the digital approximation of rushing to the store to get a copy of a highly anticipated album: Right after you bought it, you ran home, ripped open that plastic, started listening, and, shortly thereafter, talking to your friends about it. This interaction isn’t just a relic of the CD era, it’s something that still happens around marquee releases and surprise drops, but is all too often the domain of the already famous (Beyonce and Drake spring immediately to mind).

Artists of all scales should be able to meaningfully engage their fandom around each new release without having to pray for TikTok’s algorithmic mercy. In an era that will demand direct engagement to build lasting audiences, Droplink empowers artists to understand their fans and cut through the clutter.

Sign up for the Droplink Beta here.

As ever, playlist for your troubles. This year I’m not going to bother with some semblance of sequencing or theme, I’m just dumping songs I love on a long list.