Applied Science #4: Record Deal Simulator

“It’s a numbers game, but shit don’t add up somehow” - Mos Def

CLICK HERE TO VIEW DEAL SIMULATOR. READ ABOUT ITS ORIGIN BELOW.

Last Thursday, Kanye West shared his record deals on Twitter, individually tweeting the 113 pages that have molded and governed his recording career. This document dump came in the midst of Kanye’s two week crusade to free himself from his record deal with Universal Music Group-owned Def Jam and his publishing deal with Sony ATV. Spiked with some classically bombastic one-liners (“i don’t speak to non-billionaire employees,” a dig as amusing as it is tone deaf), Kanye’s contractual bloodletting and executive callouts came in a typical stream-of-consciousness flood. He punctuated his outpour Sunday with his “new guidelines” for the music industry—demanding greater equity and clarity for artists (though producers and songwriters are notably absent from West’s chosen people) beginning with plain language contracts.

The call for simplification makes sense by any objective standard: West’s deals are a quagmire of legal language, stipulation labyrinths governing advances, royalty splits, label services, and artist obligations. Put plainly, they’re complicated as fuck. Almost all these deals are gnarled texts with sharp teeth, designed for corporate protection and profit. If you know how to parse reality from the dense, comma-ridden sentences on the page, you probably went to law school (which also doesn’t guarantee you’ll actually understand) or you’re like me and had the good fortune of lawyer friends who slid you deals and explained details at early stops in your career. Even then, the intricacies of contractual English can send your head spinning.

(The simmering hypocrisy of Kanye calling for greater transparency while also having artists signed to his numerous GOOD Music joint ventures has not been lost on the social media peanut gallery, nor does it seem lost on Kanye’s inner circle or Kanye himself, as he announced he was returning his net profit share of his signings’ masters yesterday)

When we started CreateSafe a few years back, one of the goals was the development of tools to help artists, producers, songwriters, and their teams gain greater insight into their business and the industry at large—to support the power of their voices with the tools to do good, protective business. While the sort of transparency that Kanye shouts about now might feel conceptually bold and novel, it is simply the loudest and most recent call in a storied history of creatives battling for equity (the long-running battles of creatives like Prince, De La Soul, Frank Ocean, Imogen Heap, and Taylor Swift, to name but an unrepresentative few) and an emergent push for clarity and ownership amplified by tech companies (Kobalt, United Masters, Splice, Stem).

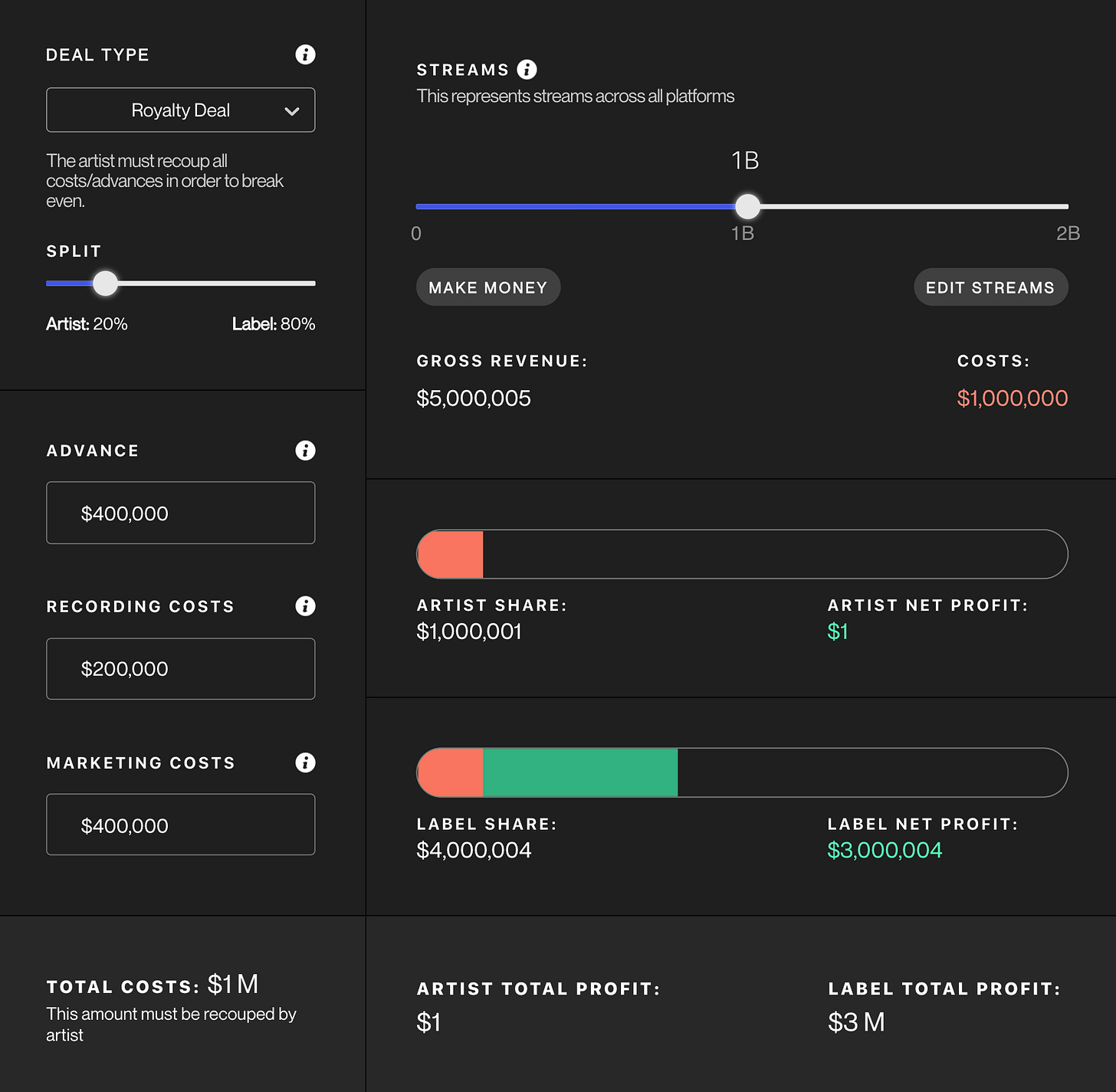

In May, we started work on our Deal Simulator, a tool meant to illustrate the economics of different types of record deals. It started months prior as a simpler tool showing how advances typically get divided by an artist’s team. We set out to build a calculator that reduced sprawling complexities to one elemental question: What does it take to make money in a record deal? This calculator doesn’t lay bare the definitive financial realities of a record deal, nor does it encompass other tricky deal points (like term lengths, 360/ancillary rights, collection periods, or delivery and release commitments, for example). It is designed to show how the math works when an artist signs—the path to profitability for creator and company alike, based solely on streams. Put bluntly: You probably shouldn’t use Deal Sim to figure out if you need to audit your label, but it can help you discern if something isn’t adding up.

[Above: A close-up of our Deal Simulator]

Royalty deals comprise the most common deal framework in the record industry; naturally, that’s where our Deal Sim starts. A new artist’s starting royalty is around 16-18%, escalating as they move through a deal’s option periods and gain negotiating leverage (you can see this to a degree in Kanye’s deals). The most fashionable current label deal for in-demand artists is a 50/50 net profit split deal, wherein costs are recouped flatly (after the label takes a distro fee) and profits are split after cost reductions. If you want a better split (60% and above), you're typically looking at a distribution or label services deal, where recoupment can either be handled in traditional royalty style (expenses recoup out of the artist’s share of royalties) or in net profit form (expenses recouped more logically from revenue earned). You can play with each deal type in the Deal Sim, though at present we don’t have functionality for setting terms like deal length, delivery commitments, sync license rates, and other granular details. Those aspects will come later.

A combination of factors determine advances and expenditures in each of these deal types: an artist's existing sales history, the competitiveness of a deal, a label's appetite for risk and investment, an A&R’s excitement about an artist’s music, an executive’s long standing relationship with an artist’s team (or lack thereof). If an artist is in a royalty deal, it enables the label to feel comfortable investing more; financial windfall goes back primarily to repaying the label's expenses (rather than the artist's advances). Broadly speaking, labels prefer royalty deals because they'll earn far more in success than they would in a net profit split deal—which they see as justification for deep initial investment. A lot of artists do remain unrecouped for long periods of time, but once things turn positive, they rarely go backwards. When Kanye speaks of the inequity of record deals, much of his anger comes from the lopsided nature of profit in royalty deals; what it ignores is the expenses incurred to reach that profit (and also the fact that, in Kanye’s case, those expenses helped provide him with a platform through music to become a billionaire sneaker mogul).

We built the Deal Simulator to give artists and their teams greater insight into the deals they could and should be doing—to give them an understanding of their worth when stepping to the negotiating table. Conversely, Deal Sim could also serve to educate people on the other side of the divide, the A&R’s and marketing executives making decisions about music they’re investing in (and also understanding the crushing debt burden that can throttle artists practically and psychologically). On either side, you’ll likely see some sobering scenarios that give visual clarity to realities you’ve read or heard about—situations made painfully abstract by the nature of contractual language.

Years ago, a high powered lawyer (the kind with their name in the firm’s name) gave me guidance that changed my understanding of music contracts. He said that record and publishing deals could essentially be boiled down to three factors: time, terms, and money.

Time: the length of the deal, whether determined in years or inferred from the number of projects an artist must deliver.

Terms: the stipulations that dictate everything from royalty rates to releasability (labels and publishers often reserve the right to not accept music they don’t consider “commercially satisfactory,” which, as you can probably tell, is a trap).

Money: advances, budgets, funds—anything you can put in your pocket or put towards your art.

He told me that in most negotiations you can hope to get two of the three at best. Artists with little to no leverage might get one of the three (typically money, which is often lavished on the naive as a mask for injurious terms), while only the biggest of stars tend to get three out of three. The broad lesson: you typically have to give in order to get; creators often must sacrifice significantly to gain attention at scale, making decisions they may not fully understand (or, if they understand, decisions that have long lasting implications they may not be able to predict). This pragmatic negotiating advice also suggests an adage I’ve learned to hold true over my career: the only real leverage anyone has is saying no and meaning it.

For the new age that we’re entering, I think these pillars can be understood as control, support, and profit.

Control: the ability to determine what you want to do with your art and how you want to do it.

Support: the services, budgets, and team members to execute an artist’s vision.

Profit: the ability to make money off of your art (or, at very least, to clearly understand the road to profitability) and levers for constant, efficient reinvestment.

Deal Sim is a tool built with the first and third in mind, an attempt to give artists and managers the sort of modeling visibility labels often hold and hide behind tangled legal language when they assemble deals. It is a tool that will evolve over time to provide more comprehensive insight; version one is a necessary step in helping artists peel back the curtain of an industry designed to extract.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW DEAL SIMULATOR.

Normally I share a playlist in this space, but today I wanted to highlight an artist with whom I work closely named TOBi. We’ve worked together for over three years and it invigorates me daily to see him hone his message and art week over week, evolving in real time. I have much to say about the determination and commitment it has taken for him to get to this place, the creative development he has dedicated himself to over the last few years and the growth he has achieved through tireless work and study. That’s for another moment. For now, I want to share his new single “Made Me Everything” (produced by Alex Goose & Ace Harris), a moment of joy and strength in a devastating time.

always quick to click that email notif when it pops up.. great read and awesome website