Applied Science #1

“Hood phenomenon, the Lebron of rhyme, hard to be humble when you stuntin' on a JumboTron” - Kanye West

In the music business, we tend to look inward for solutions rather than outward. That instinct often results in gossip, bad action, and shortsightedness. We end up repeating the mistakes of our predecessors. We narrow our world views, focused on hit records at the expense of sustainable systems and lifestyles.

Reading books and articles specific to the music business can be helpful, but sometimes it pays to step outside the frame. So this is Applied Science, an attempt to thread my concerns through problems, solutions, and concepts from other thinkers and fields. I’m trying to unearth the human aspects within the machinery of the music business, and turn some of my experiences as a manager and label co-founder into working philosophies that others can use to understand and solve their problems. I'm not sure I'm going to solve anything here. I hope I'll spark some questions, some debate, and maybe reach some people that can help enact change. It’s an experiment.

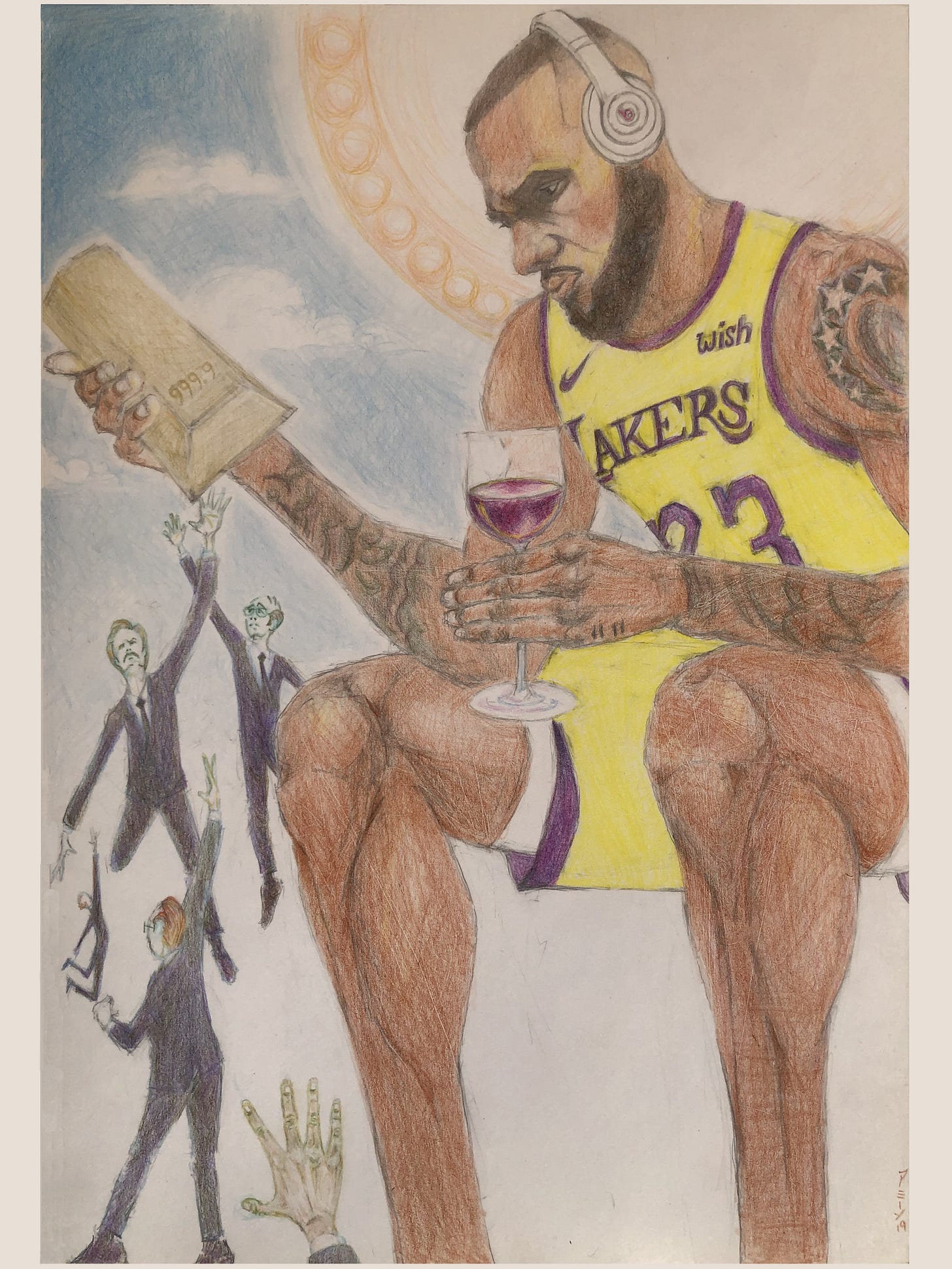

“LeBron James changed the game, but in a different way. James isn’t just his era’s defining superstar—he’s his generation’s Prometheus. Like stealing fire from the gods to give it to humanity, the changes James wrought became tools that others have wielded…These are LeBron’s twin innovations: the strategic use of contract length to maximize leverage and a comprehensive media strategy that takes player content directly to an audience. In a sense, both devices flow from the same impulse: to control the narrative.” - Jason Concepcion, “The NBA’s Prometheus”

In March 2019, Billboard announced a new marriage: Cuco, a rising indie artist, and Interscope, a label that has long prided itself on doing innovative business with artists who push the envelope (and also Maroon 5). The article highlighted the unusual nature of Cuco’s deal: a “seven-figure” arrangement in which he retained ownership of his master recordings. The key quote of the story comes from Cuco’s manager (and admitted colleague of the author) Doris Muñoz:

“‘[Cuco] owns all of his masters,’ says Muñoz of the Interscope deal, adding that the contract as a joint venture license is a healthy seven-figure deal, which includes owning his own music 100 percent. ‘We didn't want to do a typical record deal. It's been that way and that's the way it will always be. Ownership was the important factor in moving forward with the deal. That makes me so proud that we were able to make something like that happen. Omar didn't have to feel like he was signing his life away with this deal. It feels beautiful.’”

Why does owning your masters matter? Why is it something rappers have rapped about for decades—something that incited Prince to write “slave” on his cheek in protest of Warner Brothers? What does it mean to license your masters? Historically, the master recording was the recording from which all other derivative records, tapes, and CDs were made—the original copy, patient zero in the reproduction process. In the abstract, control of the master represents an artist or company’s right to reproduce that recording. A license agreement means a label only has the right to exploit a master for profit for a set period of time, but does not actually own that master. So, if an artist like Cuco owns their masters and licenses them to a label, that means someday those masters will return to them and they can re-release them independently, release them with a new label partner, or bury them in a vault (physical or digital), never to be reproduced again.

Cuco’s announcement spread fast across my Twitter and Instagram feeds. It marked the most recent flare of independent sentiment and practice exhibited by artists as varied as Chance the Rapper, Frank Ocean, the late Nipsey Hussle, Russ, Charlotte Day Wilson, Omar Apollo, Noname, and Denzel Curry. These are artists whose rejection of, or partnership with, labels rests on principles of control and ownership. This list is only partial, but speaks to a growing contingent of creators looking to exert dominion over their value, perceived and real.

Chance and Ocean ushered in a modern fascination with the liberated artist. Chance famously built a vocal campaign of his independence, pitting himself as the people's champ lighting an alternative path to (and against) the major label system. It worked: Myth-building and a hit single (“No Problems”) resulted in a Best New Artist Grammy. Ocean pulled one of the great coups in music history. On August 19, 2016, he released “visual” album Endless, satisfying his contractual obligation with Def Jam. The dust had hardly settled a day later when he released Blonde, the 2016 masterpiece he owned and released via independent distributor Stem.

The notion of creative and commercial control that Muñoz describes isn’t new. Frank Sinatra sought to wrestle creative and commercial control from the hands of his label, Capitol. The resultant struggle led to Sinatra founding Reprise, his genre-defining label which would eventually partner with behemoth Warner Records. Ray Charles left Atlantic in the 1960s to do a deal with ABC-Paramount that afforded him ownership of his masters, complete creative control, and the ability to start his own labels. Stevie Wonder negotiated a $10 million deal (that included ownership of his masters and publishing) on the verge of releasing the string of 1970s albums that cemented his legacy as an icon. Prince loudly battled vampiric label practices. After leaving Warner Brothers in 1996, he signed a series of distribution deals with different major labels (meaning he maintained ownership, but utilized the label’s services to push his music). He chipped away at the totemic Billboard charts in the process by popularizing the album/ticket bundle with his 2004 hit Musicology. This year, Taylor Swift’s battle over her existing masters and her new deal with Universal Music Group made big headlines (and stirred considerable controversy). Though specific deal points weren’t made public, Swift posted a note on Tumblr detailing that “she will own her master recordings going forward, and that UMG will share with artists the proceeds from the expected sale of its Spotify equity, and make them non-recoupable against the artists’ earnings” (from Variety). That last bit added a new wrinkle to the notion of capturing all the value an artist’s music generates, as Swift’s deal acknowledges that Spotify’s worth and UMG’s Spotify profits wouldn’t have been realized without Swift and other artists.

Control and ownership are central to these stories, but so is cooperation and collaboration with major labels—or, at the very least, labels like Motown and Warner Records that had significant commercial footprints (and the marketing leverage that accompanies a long commercial shadow) in a time before three big, mushy conglomerates made up the major label landscape. Equally key is an artist understanding the value of their creation, leveraging its worth in order to negotiate the best outcome, as Swift did. Historically, this kind of control has been the domain of the megastar. While that’s still primarily true, the battle lines have shifted. Artists and their teams have developed a better understanding of what to demand, while labels trip over each other to sign acts in pursuit of market share. Artists like Chance and Frank inspire as label-defying trailblazers, but Cuco and Russ may be more informative examples. In their own ways, the latter two used budding, rabid fanbases and healthy streaming numbers to secure artist-friendly situations (Cuco’s described at the start, Russ’ a 50/50 profit share that Russ has spoken about at length online as a true partnership).

The announcement of Cuco’s big deal echoed Russ’ nearly concurrent comments about success and control in an industry that has so often derived profit from artists at the expense of their personal subsistence: “The music business isn’t set up for the artists to get rich,” he said on Twitter. “It’s set up for everyone else to get rich off the artists. Take the power back. Artists are the nucleus. Everything and everyone else is interchangeable."

As a manager and co-founder of a label, I live on both sides of a tangled philosophical divide—one that forces me to think about comments like Russ' with a real critical remove (rather than with reactionary derision). Because Russ is mostly correct, just as Prince was correct in critiquing predatory recording contracts (which, it is also worth noting, disproportionately affect artists of color). As a manager, the burden rests on me to figure out the best situations for my clients—to defend their rights, their intellectual property, their ideas. In many cases, I’m also a sounding board and a creative confident, a collaborator helping bring ideas to life. As a label partner, I balance making the best decisions for the label while proposing more equitable realities for the artists we sign (though, admittedly, there are difficulties in this mission that are inherent to the major label joint venture structure that, frankly, would require an even longer piece to dive into). I believe the value proposition of a modern record label must evolve from catalog-owning intellectual property fortress to creative agency with promotional services. This shift is already happening, but deal structures don’t often reflect the change. Many managers have already adapted to this new reality, becoming full service artist support systems that help mold career trajectories before a label gets involved (if ever).

[I could go on at length about the philosophical balance of being a manager and running a label, as well as difficulties of changing what it means to be a white co-founder of a label that profits primarily from the music of black artists, but these are topics that require their own full space to unpack.]

Russ' tweet reminded me of Lebron James’s professional journey. Since the waning days of his initial campaign in Cleveland—perhaps as early as the 2006 Olympics—Lebron’s awareness of his tremendous worth powered his choices. Lebron’s talent, popularity, and titanic celebrity enabled him to make The Decision on national television. This reshaped the course of the NBA by popularizing the “super-team” movement, and spurred a spate of player-led demands and moves crushed by owners and commissioners in previous eras. It also turned Lebron into a divisive figure lording over a controversial age. It spurred debate about the legitimacy of super teams—and argument about his legacy. People burned jerseys (always a stupid act, made to look even stupider when Lebron returned, and made even worse by the plantation owner mentality embodied in Cleveland Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert’s infamous letter). The furor likely made Lebron even more famous and influential.

Whether you hated the moment or celebrated the man, Lebron lit a new dawn with The Decision. He created a platform (and essentially forced a major network to broadcast it, knowing it would be appointment viewing). He made a spectacle. He tried (and largely failed) to control the narrative. He sketched a blueprint for something to be built later and more effectively in his budding media network (The Shop). In the process, Lebron emboldened his contemporaries, setting off an age of player liberation and unprecedented collective action against owners.

We have entered the Lebron James era of the music business, where artists must understand their worth and their strength, as individuals and as a loosely unified whole. More companies profit off of and use music than ever before. No time in human history has boasted more television shows, more concerts, more advertisements, more “content,” and simply more places to hear music. The hunger for new music (as the hunger for new content across all media) is unquenchable, unrelenting. For emergent artists, there is power in patience, power in defined vision, power in trusting your instincts (even when they lead to mockery and outright hatred), power in defining a voice and vision, in telling stories and transmitting your personality across your platforms of choice.

Past eras have painted the battle as independent versus major. That felt truer in an age when the Sex Pistols, Ramones, NWA, and Public Enemy could snarl, enrage, and prod their way to national stardom. Now—as the tendrils of commerce and corporations insinuate themselves into almost every aspect of publicly consumed art—it’s less about being independent from a system and more about using the value of your intellectual property to make existing and future systems work for you.

[For those out there that think the above is a dark, shudder-worthy statement: You’re absolutely right. The whole system is infected, likely beyond repair by anything other than the sweet release of complete destruction and rebuilding. I’m not really here to argue about “real” art and whether or not art with integrity can be created in a climate struck through with commerce. This piece is an attempt at optimistic pragmatism, with an eye towards a better future as more creators awaken to their power.]

Russ’ summation of the music business is right, but only partially so. Independence is not binary—it’s a matter of degree. It is a game of control and flexibility—degrees of freedom. How much are you willing to give to amplify your message and achieve your desired ends? Do you know (with clarity) what those are? In modern life, you are typically at the mercy of one publicly traded corporate beast or another. Unless you plan to press vinyl yourself and sell it directly to consumers (and also you own the vinyl pressing plant where you press that vinyl and you don’t use the internet and you are some sort of really industrious hermit who just built all this crazy shit yourself and somehow has fans to buy your music), then it’s hard to say with complete accuracy that you are “independent.” That’s why Russ’ notion that “everything and everyone else is interchangeable” feels a bit reckless: it is specific to his experience as a business-minded creator with a storied (and oft-derided) pension for doing everything himself. Lebron would still be a titan without Maverick Carter, Rich Paul and Worldwide Wes, but with Carter, Paul, and Wes, he channeled his generational talents to build a burgeoning media empire sporting lucrative partnerships with Nike and Warner Brothers. Many artists need teams to execute their visions—to not only help with the grunt work (posting and optimizing YouTube videos, overseeing tour logistics, helping issue takedowns for bootleg merch), but to help amplify their clients’ vision through ideation, relationships, and big picture planning. The artist’s creation is the genesis.

“And we salute King James for using his change/ To create some equal opportunities” - Anderson .Paak, “King James”

Lebron’s narrative serves as informative inspiration for ways to navigate the modern landscape as an artist concerned with control and ownership. He used the NBA’s need for entertaining stars to his advantage, setting a blueprint to be built on by others around him (and hopefully for the collective good of all players going forward). He set an example for those looking to profit off of their talents on their own terms, while acknowledging that it still requires engaging with existing systems to amplify their ideas and grow their business. The point: engage on your own terms and make the system work for you.

NOTE 1: A corollary read to this week’s edition is a thoughtful piece by the NYT’s Marc Stein from July 8 that has an unfortunate headline, but gives a good overview of the NBA’s current business playing field and touches importantly on a dynamic as relevant in basketball as it is in music: “There is another dimension to the power dynamics [NBA Commissioner Adam] Silver is bound to be asked about: In a league in which three-quarters of the players are black, some have pushed back on the very term ‘owner’ as outdated, offensive and feeding a tone of servitude.” It is worth noting, in this celebration of Lebron’s empire-building, that he does not yet own a team (a symbol of wealth still reserved mostly for titans of industry, and still the overwhelming domain of white men). Undoubtedly, that day will come for him if he wants it, as it has for Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson.

NOTE 2: I wrote this before Lebron’s muddled, misguided comments on China—or, at very least, misguided for a person who has consistently pronounced himself a proponent of social justice. I suppose this is the tangle of capitalism and the vocally ethical superstar. While his comments are still not quite as cynical as Michael Jordan’s apocryphal “Republicans wear sneakers too,” they point to a man who perhaps occasionally wants to protect the purse at the expense of his personal philosophy (unless, to this point, he’s viewed relative outspokenness and anti-Trump sentiment as good marketing). While I believe he can recover, Lebron’s China comments do cast a shadow on his previous words and actions. They don’t undermine his importance, they don’t tarnish his legacy, but they do form a curious crack in an otherwise strong social resume of a superstar athlete.

NOTE 3: There’s a larger debate here to be had about whether you can ever change a system from within or whether change has to come from scorched earth and complete rebuilding. For another time.

If you made it this far, you deserve some fucking music. This week’s favorite songs come from varied corners of the R&B landscape. One standout I keep coming back to is Atlanta singer Mariah the Scientist’s “Beetlejuice”—hypnotically reminiscent of Frank Ocean (name-checked in the song) singing over “Hotel California.” It’s been on repeat since late summer. Detroit singer/producer Choker’s “Guava Tea” is a lovely three minutes in which to lose yourself—an intimate and endearing bit of writing that sits nicely next to the stunning, recently unearthed acoustic demo of Prince’s “I Feel For You.” And more Brittany Howard this week. Her album Jaime is probably my favorite of the year. “Goat Head” is its stunning centerpiece. Lastly, one of my favorite producers ever returns in vintage form this week. Clams Casino is back with a song called “Rune,” and it’s basically what you want if you’ve been a Clams fan for nearly a decade (as I have). Here’s a playlist of some of these things and more (I’m just going to keep adding to this playlist and sequencing it as if it’s meant to be listened to in order; there is loose stylistic rhyme and reason to it, but it’s going to get pretty long until I decide to trim it).

Powered by CreateSafe.